Meet the preLighters: an interview with Tim Fessenden

10 March 2020

Tim Fessenden is a postdoc in the Spranger Lab at the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cambridge, MA, USA. He studies how immune cells put themselves in the right place at the right time to initiate anti-tumour immunity. We caught up with Tim to discuss his research, science communication and preprints.

What inspired you to study biology and then start your career in cancer research?

As a kid I liked going out in the yard of our house and doing stuff like stare at the dirt with a magnifying glass; and because I’ve always been interested in biology, it was easy for me to feel motivated to study it at high school and later at university. During my undergraduate studies, I took a cancer cell biology course and it amazed me how cancer cells can do all the same biology as normal cells, but then they also do some things differently, which leads to disease and altered tissue states. The course, which was taught by a great professor, really turned on my intellectual curiosity, so it was one of those things when you have a good experience and that really sets you up.

Before starting your PhD, you first became a research technician in a lab. Why was that?

The reason for that was I didn’t do research during my undergrad and I knew I wouldn’t be as competitive for some PhD programmes without the research experience. I had already graduated, I was painting houses and working at a bar and wondering what I was going to do, so that sort of motivated me to figure out any way I could possibly get into a lab. I also wanted to know if I would enjoy research before signing up for a whole PhD.

After studying cell motility during your PhD, you transitioned to the immunology field. What was that like and what were your reasons for changing research fields?

It was not easy. It was very unclear to me what I should study because I was a little bit frustrated with the field I was in for my PhD, where I was doing hardcore biophysics and actin cytoskeleton stuff. I felt that I needed to bring back the focus to cancer and biomedicine, because that was really my background prior to my PhD. But I had no idea how I could do cool things with cell motility using a lot of microscopy, and still have a more biomedical and cancer-related focus. Immunology just never really occurred to me before as an interesting field; since immune cells don’t have the kind of adhesions and structures we cared about in my PhD lab, they were never considered [laughs]. But then when I saw a talk from Stefani Spranger, my current advisor, it really set off all these alarms in my head. I realized that immunology could unite the two things that I really wanted: to study how cells move around and the mechanics and physics related to that, and do work that has major relevance for cancer therapies. It’s amazing how this one moment changed everything for me and made me switch; after I saw Stefani’s talk I went up to her and we started chatting, and that’s what then led to my postdoc.

What are the scientific problems you are now working on in your postdoc?

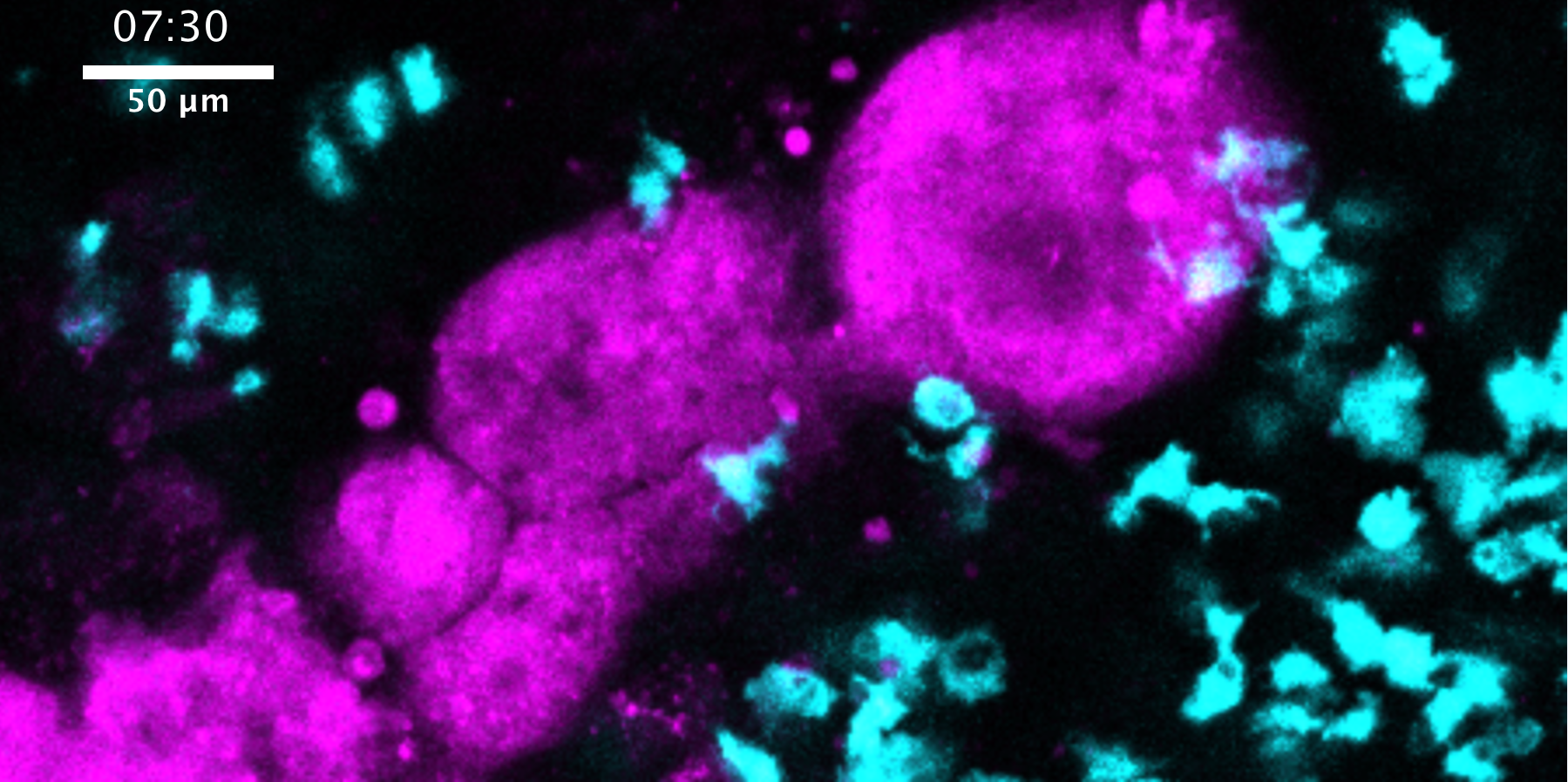

Immune cells function as part of an organism-wide system, so to take out cells and try to study them outside of their physiological context poses huge challenges; and there is so much that immune cells do in vivo that we have trouble understanding! We study dendritic cells (the sentinels of the immune system), which activate T cells and the adaptive immune response when they sense danger. The timeline you get from a textbook is that the dendritic cell goes into a tissue and then it moves to the lymph node where its job is to activate T cells, and after that all we care about are the T cells. But in fact, dendritic cells remain in the tissue (in our case the tumour) as well, and immunology doesn’t have a good answer to what they are doing there and what effect this population of dendritic cells has on the immune response. This is just one of the examples, but in general, finding cells in new places where immunology says they shouldn’t be or has no idea why they are there, and figuring out what they are doing are the kind of open questions that I’m really focused on.

You started your postdoc in a brand new lab. Could you reflect on the advantages and challenges of joining a research group of a junior PI?

So the cool things are that I’m the same age as my mentor and this makes it feel more like a collaborative relationship, which is really nice. She and I are bringing our expertise from our previous research fields together to push forward the projects in the lab. She is very accessible, so I can just run into her office and ask her a question, and the communication between us is very easy and frequent, and I really appreciate that – after my PhD it was clear to me that I wanted to join a lab where I was closely working together with the PI.

I was also heavily involved in setting up the lab, which was really fun; for example, I was instrumental in getting the department acquire the microscope we use. A lot of my time in my first 6 months went to basically testing and working with Leica to set up this new microscope, and giving examples and testimonials so that the department would agree to make this purchase.

Regarding challenges, there are always going to be some on the way, as I’m learning to be a postdoc and Stefani is learning to be a PI, so this is really a shared learning experience. Having worked in a big lab for my PhD, I realized my mentor’s name in the field just did a lot of work for me, because people often do mental shortcuts; in a junior lab, you really have to get yourself in front of people and get them excited about your data and research.

You obviously enjoy the communication part of science, as you’ve written blog posts for The American Society for Cell Biology (ASCB) and are running a science podcast. Could you tell us about GLiMPSE and how you got into it?

I was listening to podcasts already, and I have so many friends from my PhD program and here at MIT with whom I love to discuss about science. I’m always curious to hear and learn new things – how research happens in different fields, what sort of challenges people face and how they overcome them; this made it really easy for me to get excited about doing podcasts and join the GLiMPSE team. It’s currently three of us who run it, and each one of us has their own style. Sometimes setting up and doing the interviews is the really fun part, but then the editing afterwards can take a really long time. It’s been a big learning curve – learning how to use the software and what sounds good to a listener. But it’s a lot of fun. I’m actually just working right now on an episode of a live event we did with a really wonderful and amazing scientist, Angelika Amon.

Why did you join preLights and what’s your experience been like so far?

I think preprints are helping move publishing and communication of science in the right direction, so to me it really makes sense to invest in them. I also enjoy writing and have opinions about the preprints that I read. But in my view, it also takes a lot of time to write preLights post, because to come up with good questions I read the work very carefully, and look at the work that the authors cite and some of the previous publications of the lab. It was rewarding when one of the authors wrote back to me that “it’s so nice to read these questions because it tells me that you really understand this work”.

What is the adoption of preprints like in the immunology field?

It’s a more traditional and conservative field, which I think shows when you look at the distribution of preprints through all fields. But there are definitely some good labs putting out their work as preprints on a consistent basis, and I think as more big labs follow, preprinting will become normalized. It’s hard for me to really pinpoint why a field would be more resistant than another to preprint; there are probably multiple reasons. I think those fields where there is more perceived risk of scooping, and more emphasis placed on secrecy and concern about confidentiality, will obviously find it harder to accept preprints. But I hope it’s just a matter of time until people will realize, as they do the logic, that these things are not a real issue with preprints. And I’m really eager to be part of the change!

What are your future plans?

I like research a lot and I like teaching, so my plan A is a faculty position at a research institution. If that doesn’t work out, I would be happy in a teaching role, for example at a non-research university. Nothing is guaranteed, but what’s important to keep in mind is to have fun along the way!

Finally, what would people be surprised to find out about you?

As I mentioned before, I didn’t do any research during my undergrad, and that’s because I double majored and was much more focused on the humanities. I spent most of those years at university really focused on the social change and identity politics for gay and lesbian youth. I did an internship in Berlin and one in San Francisco, I was embedded in non-profit organizations and I wrote a thesis on the topic. It was at the end that I spoke to a philosophy professor who suggested that I go and figure out the science first, and this helped me make the decision on which path to take.