preLights talks to Professor Christopher Jackson

25 October 2021

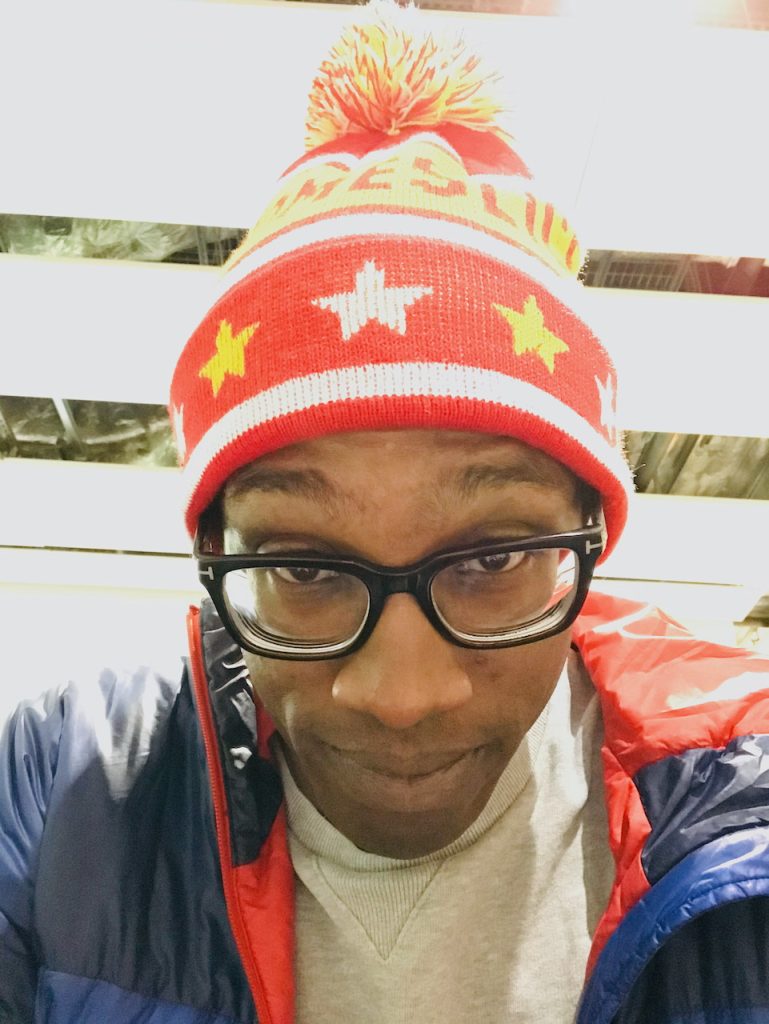

preLights talks to Chris Jackson

Chris Jackson is Professor of Sustainable Geoscience at the University of Manchester, UK. Alongside his research career, you might recognise him from his TV work: he presented The Royal Institution’s 2019 Christmas Lectures as well as BBC2’s Expedition Volcano, which showed him descending into Mount Nyiragongo in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Chris is also a big proponent of preprints and was one of the founders of EarthArXiv, the preprint server for research in the geosciences. We spoke to Chris about his research career, science communication work, and why he advocates for preprints.

What led to you pursuing geology to begin with?

I was a bit rubbish at everything else, so that was a strong motivation! I did enjoy the subjects I did in school and I did OK academically, but I was never particularly inspired by them. In fact, one of my worst GCSE grades was in science, second only to French. So, I didn’t really start as a scientist at all, and I think that’s because a lot of the things I was learning were quite abstract. When it came to geology, it felt more like it was this natural world framework for all the amazing things around us. But my mind worked in a way that needed a provocation to go and do something, which is why I made the decision to go to university quite last minute. I went to a tertiary college, as my school didn’t have a sixth form, and it really ended up with someone saying, ‘why don’t you go and study this?’ before I realised it was an opportunity to go and learn more about something I found interesting. I hadn’t even coupled university with being a part of education before that.

I think it’s important for people to remember that we’re not born scientists. You can fall into certain disciplines through your experiences and your interactions with individuals who inspire you, and I like that. I like the idea that you don’t need to have been playing with rocks in the sandpit at the age of five to go into geology. It can be different from that, and it was for me.

You did your undergraduate degree and your PhD at the University of Manchester. Did you enjoy your time as a student in Manchester?

I had a really good time. I was really into going to nightclubs so it was an ideal city for me at the time – I could offset the academic endeavour of going to university with the very involved social existence that I had. It was really important to me that the environment was right to support my learning, and I just loved it. And that’s why I started to do the PhD – I just thought the city had loads of stuff going on, it’s really fun, and I could look at rocks at the same time!

Overall, my PhD was a nice time. I think there were some issues I had with lab mates, and looking back now I realise that’s partly due to their background – they’d been to Oxbridge, and then there were those of us who hadn’t. There was a bit of a gulf there, but it’s only now that I’ve realised why that might have contributed to the friction in some of those lab relationships. But I did have some very good friends there as well.

You spent a lot of your PhD working abroad – can you tell us more about that?

I did a lot of field work in Egypt, including the Sinai desert. I was based along the peninsula between Sharm El-Sheikh and Suez, in a fairly isolated location. This was before we had mobile phones, before we even had digital cameras, so it was quite a testing environment. I also spent quite a lot of time in Cairo, which was quite hard at the time. We had support from the local energy company and we were there to train their staff in field skills. We had some instances when we were working during Ramadan, so the staff were fasting in the field – it was 35, 40 degrees and they couldn’t eat or drink in the day. It was an interesting cultural learning time for me to see how people made their religious observations in very physically testing environments.

I think I grew up a lot during that time. I was 21, 22 years old, living in an incredibly busy city, and the nearest internet café was a two-and-a-half mile walk away in a shopping centre. It was good fun, but the conditions were challenging and it was quite difficult being away from everyone back home.

After your PhD you started working as an exploration research geologist in Bergen. In biology it’s quite unusual to move back into academia from working in industry – is that the same in the geosciences?

I think it’s equally unusual, but it just happened that way for me. I went into the energy industry, which I kind of liked, but didn’t like some parts of it. My girlfriend at the time couldn’t get a job in Norway and came back to the UK, so in the end I came back to try and get a job in the energy industry over here, but I couldn’t find one. I ended up taking a one-year maternity cover role at Imperial College London, and 17 years later, here I am.

I had no intention of staying in academia, but I think I’m a bit more at peace with the position I have because I have worked outside academia and have a sense of myself as a non-academic. Referring to your question, it is quite unusual for academics to step out and back into academia, and I think that’s for various reasons. Competitiveness as much as anything. And perhaps aspects of feeling ashamed because of the discourse around it being ‘better’ in academia or ‘better’ to be a scientist outside of academia. I think being outside of academia allows you to get a sense of yourself as a scientist contributing to society and function in that different space. I genuinely think that the fast-track approach of academia with no breaks is responsible for many of the ills we do see in academia.

Do you think working in industry changed your view of science?

Yes, I think in industry it was a bit clearer: we need to drill this well, or we need to provide technical advice about getting oil, so we would do the best technical piece of work we could for that. And there was a type of peer review, called peer assist, where somebody would look at the work in a much more respectful and constructive way. The verbal language and the body language that everyone used was different because we wanted the projects to happen, and I don’t think we have that so much in academia.

There is a bizarre hierarchical scheme in industry, but all of the technical power essentially resides with the people who are pretty much at the bottom of the pile and I felt the management had better respect for those people. In academia [with respect to management] it’s literally a case of making it up as you go along.

Now you’re back at the University of Manchester as the Chair of Sustainable Geoscience. For us biologists, can you explain a bit about what sustainable geoscience is?

I always explain this by saying it breaks down into two pieces. First is sustainability: our ability to live harmoniously with the earth in terms of a symbiotic relationship with resources, and an awareness of the hazards that the earth poses as a result of its own natural functioning. How do we make sure that our relationship with the earth, the lithosphere, the atmosphere, the biosphere, is constructive and positive? And make sure that lasts for generations? And I think that’s the view of sustainability that has entered the public lexicon now.

The geoscience aspect is the study of the earth and how it functions, so when you think about sustainable geosciences, it’s how we can use geoscience as a subject to ensure this sustainability happens. So, how do we find, extract and use resources in a way that means that they will be around for generations to come? How do we use those resources – such as oil and gas – in a way that doesn’t contribute to further climate change? How do we use structural knowledge to advise where and when and how big earthquakes or volcanic eruptions might be? And how do we advise town planners where and how to build new dwellings on the planet as our population grows?

Is that a relatively new way of thinking about geoscience?

I would argue that it’s not. There are lots of people who have been working in, for example, water chemistry, and hydrology and water provision in desert environments. In volcanism and the risk posed by pyroclastic flows, this has been going on for hundreds of years. What they don’t need is someone like me coming around and going: ‘Hey! Everybody! This is sustainable geoscience but you’ve never heard of it! You can apply your skills to saving the planet!’. They’ve been doing this already. I think it gets talked about like it’s a new thing because it’s fashionable and part of the UN Sustainable Development Goals, but it isn’t like that at all.

A lot of the objectives are reimagining some of the skills we’ve developed to put them into a domain with sustainability more at its centre. For example, the techniques we use for oil and gas extraction can be readily applied to carbon storage or hydrogen storage. There’s an awareness that the geosciences are going to have a huge impact on tackling some of the big socioeconomic challenges we’ve got on the planet. To realise its full potential, we need people working in it to be able to talk to people in different parts of the world. We need to be more conversant with indigenous communities about how they view science, how we might try and put in place things that would protect them or make sure they have sustainable resources. We really need to be able to talk to people from the different global communities and we haven’t been very good at that. At least in terms of resources, geosciences have a very colonial history.

Are you quite closely aligned with policy?

Yes exactly. A lot of geoscientists don’t necessarily do it as well as we should, but there are people advising the government on these issues in the same way that a virologist or immunologist would advise on COVID-19. With a warming planet and with sea levels rising, it will be geologists who are talking to governments about policies and playing that central role.

How do you think we can promote a better perception of scientists in those roles?

I think we need to give the public and other scientists a better view of what we are in our totality. We are rounded people, we are still citizens, and we are lay people when it comes to areas outside of our specific domain. I think it’s a problem that scientists are seen as a homogenous group who have this all-seeing knowledge across all scientific domains, and what we actually have [individually] is knowledge on a vanishingly small and inconsequential topic. I think having those more honest conversations with the public would help.

I also think if we want the public to trust scientists and science-based policy, they need to see themselves represented amongst the corpus of people who are undertaking science. That means diversity in gender, sexual orientation, race and ethnicity. You cannot get the public to trust the science underpinning policy when scientists are viewed as one-note or working in the ivory tower. An integral part of our science is the translation part, having appropriate representation, and communication at all stages of the scientific process, from conception to execution.

Leading on from that – you were the first Black scientist to present the Royal Institution’s Christmas Lectures, which have been running for almost 200 years. You speak a lot about representation and diversity in science, and this is a huge question, but what can we do to make science more open to a broader group of people?

The obvious answer is just to be less discriminatory, but it’s not an easy answer. It goes all the way from the socioeconomic circumstances people find themselves in, to the racist structures that determine who gets to go to university, who gets a PhD scholarship, or who gets the postdoc or the job. All these layers present a barrier to access, but also make it a hostile experience for those who do enter the system. So, it’s not just diversity; we’ve got to talk about inclusion and making sure that the environment is welcoming.

It’s also a challenge in terms of how we design the structures by which we measure and hire people. At the moment, we’re not measuring brains or intellect or potential, we’re measuring financial advantage and access to opportunity, which isn’t reflective of any of those things. If you say that PhD scholarships can only be awarded based on specific criteria, then that disadvantages a whole group of people. If you modify those criteria to make them contextualised for the lived experience of the people who are applying, that’s a different thing. People can bring a different perspective to science, and that’s another reason why we should want them, but it does place the onus on institutions to go to work and make their environments a safe place where individuals can thrive. And I don’t think institutions really want that: they just hoover up the people who look good and let them thrive, and I think they need to do more than that.

Moving to preprints, which can level the playing field a little in terms of access to papers: how common is preprinting in the geosciences, and what inspired you to co-found EarthArXiv?

Preprinting is very new in the geosciences. A lot of seismologists working on earthquakes and so forth were already preprinting the more numerical pieces of their work with ArXiv, but EarthArXiv is the first preprint server for the geosciences. It’s a challenge, of course, because academics tend to be progressive in their science but conservative around everything that sits around the technical bit of science [like publishing]. So, it’s a case of talking about all the standard concerns that people have around preprinting.

In terms of making academia more equitable, I think preprints do a couple of different things. They open up science and make it more transparent, which is very positive for early-career researchers. I also think preprints can be used as a forum to bring people together and collectively try to improve a piece of work. Brian Nosek, who founded the Center for Open Science, made the point that transparency is a replacement for trust in science. You shouldn’t say to people ‘just trust me’; you should show people and leave your work open for their own interrogation. There are some studies that show that public trust in science is greatly enhanced by increased transparency, and preprinting is an integral part of that, as is clarity around peer review reports and clarity around funding decisions. All of these developments are part of the same thing and help both scientists and the public trust in science.

Is EarthArXiv gaining traction in submissions?

We’re getting towards 3000 submissions now, so there’s a steady stream of people submitting and updating preprints. It’s a case of getting the gospel out: telling people what it is and that it’s available. What we need to do is talk to early-career researchers, and even thought they might not have the power to go against their PIs to preprint their work, it equips them with the knowledge to do things a different way when they get into more senior roles. I also think it’s important that institutions state that preprints are permissible research outputs on job applications, and that we start pushing that language down from a high level.

To finish – what’s something about that’s surprising?

I can knit! I used to knit jumpers for teddy bears when I was little and make soft toys and Christmas decorations. I think that’s the most surprising thing about me that you wouldn’t guess!

Chris was interviewed by Helen Robertson, Community Manager for preLights. This interview has been approved by the interviewee.