Meet the preLighters: an interview with Erik Clark

15 June 2018

Erik Clark is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Cambridge in the lab of Michael Akam. Erik studied at Oxford and Imperial College London before starting his PhD, where he worked on segmentation patterning in Drosophila. Erik has won a number of grants and awards, among them the BSDB Beddington medal for the best PhD thesis in Developmental Biology (click here to see his Beddington lecture). We caught up with Erik at his office at the University of Cambridge Zoology Department to talk about his evo-devo research and his experience with preprints and preLights.

How did you get interested in biology and evolution?

I’ve had an interest in evolution for a long time; I think it started in junior school when we were learning about the Victorians. I chose to do my project on Darwin, because I’d recently seen a BBC documentary about evolution, and thought the whole thing was really cool. That’s when I learned the basics of natural selection, sexual selection and so on. Later on in secondary school the biology syllabus wasn’t very inspiring, but I read a lot of popular science books and evolutionary biology books. However, I didn’t realise that you could actually do evolutionary biology as a job until I was at university.

You joined Michael Akam’s lab for your PhD. How did you choose the topic of your graduate research?

When I joined Michael’s lab, I wanted to do some sort of modeling project related to arthropod segmentation, and I imagined that I would end up working on a species like Strigamia (centipede) or Tribolium (red flour beetle). I assumed that everything in Drosophila must have been figured out already. In my first year I was reading around, trying to find a good question, and I settled on the pair-rule genes. I remembered that as an undergrad I had struggled to understand how their patterning – going from seven to fourteen stripes – worked and thought back then that I was just being dumb. Then, digging deeper into the literature, I realized that nobody really understands how this works. So I decided that this frequency doubling problem would be a really nice, self-contained puzzle to work on in my PhD.

What’s a question in your field that keeps you up at night?

The question I puzzle over is the whole existence of pair-rule patterning. The ancestral condition in arthropods is to generate one segment at a time as the embryo grows. However, there were at least two independent events – in centipedes and in insects – that led to each cycle of the segmentation clock generating not one, but two segments. It’s obvious why this is beneficial – it speeds up the patterning of the body two-fold. But how could this change happen without also screwing up the body plan – i.e. the number of segments, and the identity of those segments? I know that the current system must have evolved gradually, and I would like to figure out how.

On Twitter you describe yourself as a developmental systems biologist. What does that cover?

In my research I am combining a systems biology perspective with evo-devo questions. Rather than just comparing expression patterns between species, I’m trying to model the underlying gene networks and figure out what exactly needs to change to result in those differences. Drosophila is a great model system for these types of studies, since there is a wealth of knowledge and data in Flybase and the literature, which really enables you to make good models. In other species like Tribolium, the important thing now is to get a lot of the descriptive research done that will enable us to make well-constrained, informative models. But the technology is there and it’s easier to do the essential descriptive studies these days than it was in the ’80-s and ’90-s in Drosophila.

How much of your research time do you spend on modeling vs. experiments?

When I started my PhD, I was adamant that I was only going to do computational stuff. But I got about a year in, and I ran out of data to analyze, as I’d worked my way through the existing literature. I had some interesting hypotheses that I wanted to know the answer to, and that’s when I decided that I would do some experiments after all – my lab mates were laughing seeing me having to learn all the basics, like what a fly or an embryo looks like in real life! The rest of my PhD was mostly wet lab, just because it took quite a long time to do all the in situ experiments and get them to look nice. Now in the postdoc and going forward, I would like to have a nice mix of bench work, data analysis, modeling, and just thinking and reading.

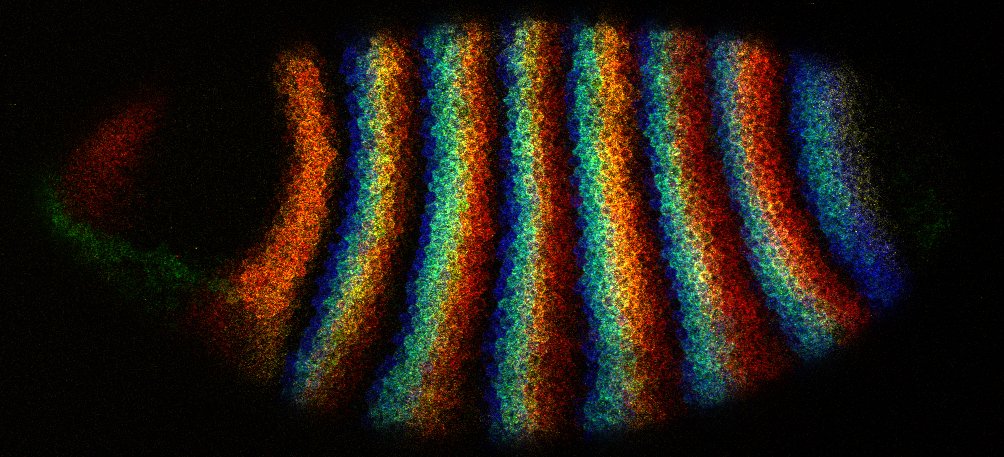

A quadruple HCR in situ image of a blastoderm stage Drosophila embryo by Erik.

The genes are: fushi tarazu (blue), odd-skipped (green), deadpan (yellow), and hairy (red).

You’ve posted four preprints so far (the most recent one was just published in Development). What first led you to put your work on bioRxiv and how has preprinting your work benefitted you?

When I first heard about bioRxiv – it was early 2016 – I was over at the Genetics Department and having tea with my boss Michael and Alfonso Martinez-Arias, who is very enthusiastic about preprints. I was writing up the first paper from my PhD, and Michael and I were also writing a grant application. Alfonso suggested we could put the paper on bioRxiv so that we could reference it in the grant. It was a great suggestion, because we got the grant and one of the reviewers specifically mentioned the preprint in their review.

Since then, publishing preprints has been really good for increasing exposure to my work and getting feedback; people are more willing to give feedback on preprints than to criticise a published paper. I also like the idea of open science and sharing things as soon as possible. On top of that I think it removes a lot of publication stress, because you know your work is out there and people can see it.

‘ […] people are more willing to give feedback on preprints than to criticise a published paper. ‘

What was your motivation for joining the preLights project? And what’s your initial experience after the first four months of preLights?

I thought that joining preLights would be a good motivation for me to read more papers, especially those outside of my immediate field; and to get some more experience in assessing papers and communicating them in a (hopefully) clear and enjoyable-to-read way. It has turned out to be really worthwhile for me, and apart from getting practice in science writing, it’s also nice getting the comments back from the authors of the preprints that I’ve chosen. People tend to be really pleased that someone has decided to highlight their work!

What’s next for you in the future?

I will be joining Angela DePace’s lab at Harvard Systems Biology this autumn. The plan is to get comfortable with the new live imaging technologies available in Drosophila, and get experience with different kinds of image analysis and modeling approaches. I’m looking forward to it.

Finally, what would people be surprised to find out about you?

As a teenager I spent a few months volunteering with the National Park Service in Arizona, building trails and fences and things. So if you’ve visited the Grand Canyon or Zion recently, perhaps you’ve seen an H-brace or drainage ditch that was one of mine.