Meet the preLighters: an interview with Mariana de Niz

7 January 2020

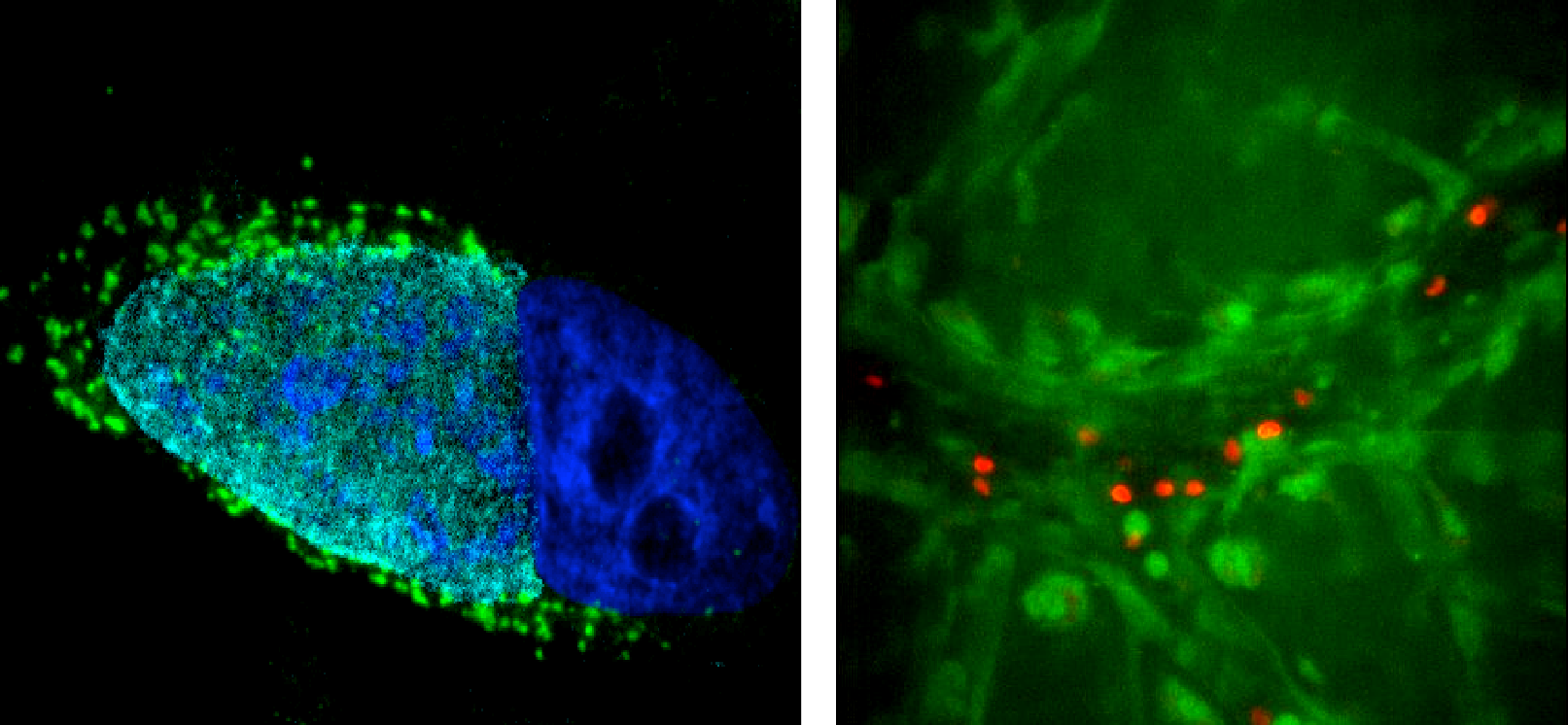

Mariana de Niz is a postdoctoral researcher in Dr Luísa Figueiredo’s lab at the Institute of Molecular Medicine in Lisbon, Portugal, where she studies the biophysics of trypanosomes in various tissues. We caught up with Mariana to discuss her experience in parasite research, microscopy, open science and what it’s like to be a preLighter.

Let’s start at the beginning; how did you become a biologist?

I don’t know if I consider myself a pure biologist. Since I was very little, I wanted to be either an astronaut (like most children!) or a medical doctor. I was always drawn to tropical medicine, so if I was going to be a doctor, it would be in tropical medicine.

Then in high school, I found out that to be an astronaut you need 20/20 vision, which I don’t have, so I sort of gave up on it around that time. It still wasn’t easy to choose what to study at university because I liked everything in high school – history, geography, physics and biology – but then tropical medicine was something I was still very passionate about. The questions that most interested me were how we, the host, defend ourselves against pathogens. After exploring various academic programs, I went to study immunology at the University of Glasgow for my bachelor’s degree.

How did you then end up studying malaria?

During my bachelor’s degree, in a particular class, the professor kept on talking about ‘Manson’s Tropical Diseases’ book, which I then started to read – and eventually was so fascinated that I read it all! I knew that my decision about what to specialize in was always going to be between Plasmodium (malaria) and African trypanosomes (sleeping sickness). But at that time most research on trypanosomes was about the molecular aspects of the parasite only – I felt that the idea of host-pathogen interactions wasn’t so well developed. However, host-pathogen interactions was already a huge field within malaria. I went to do my master’s degree at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, where I had the chance to travel to Uganda and Malaysia for work on malaria. And this was life-changing! It was actually the switch between the dry season and the rainy season when I was there; I was receiving samples from children and could see the huge increase in malaria cases. You can read about this in books or papers, but being there gave me a real sense of the level of damage these pathogens were causing.

You went to Bern for your PhD. Could you tell us what questions you were trying to answer?

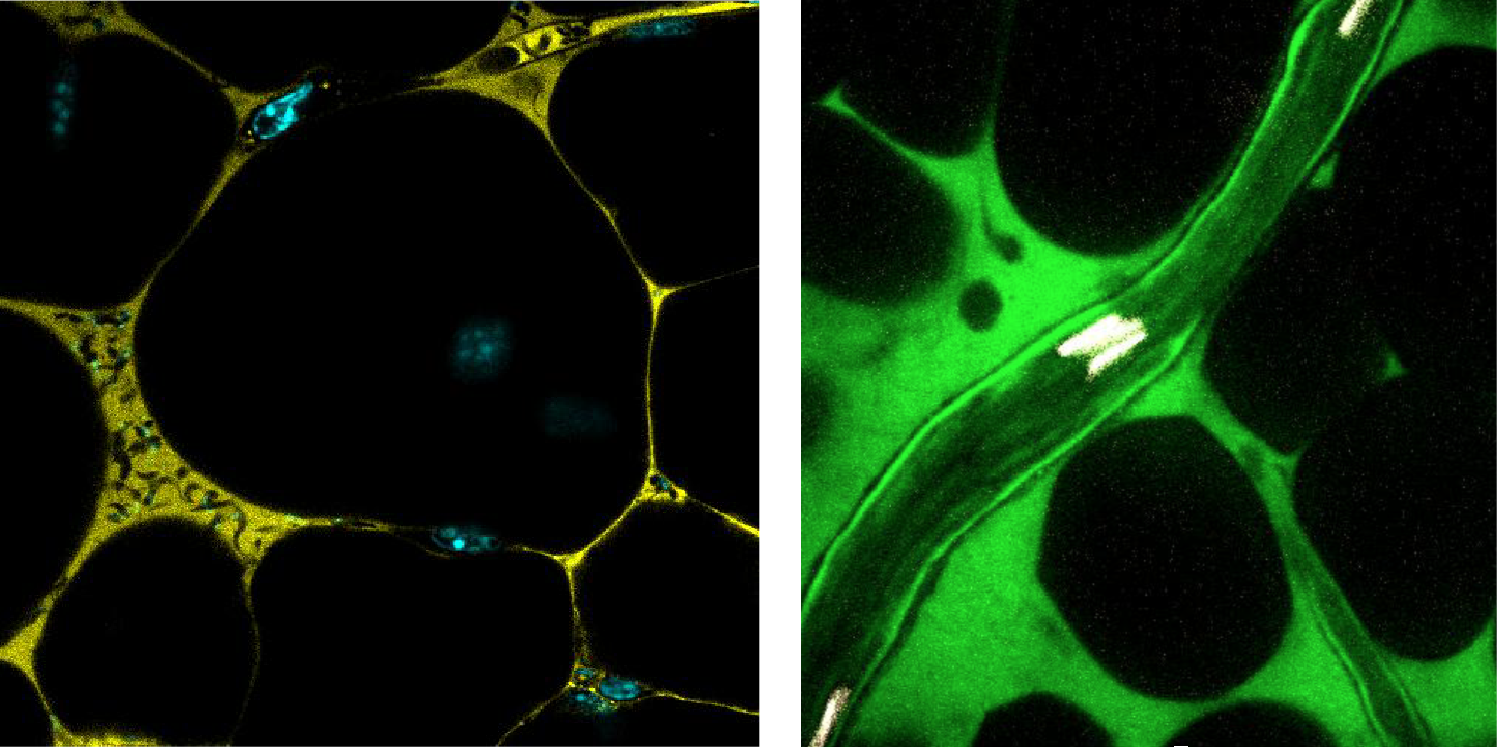

I went to Volker Heussler’s lab, which is one of the few labs that has a huge expertise in, and combines, microscopy and malaria research. A lot of the pathologies caused by malaria occur because once Plasmodium invades red blood cells, it exports virulence factors to their surface, which makes the parasite stick to the vessels of all organs. And this sticking causes a lot of damage; either it damages the endothelium and leads to haemorrhages, or it completely blocks the small blood capillaries and disrupts the blood flow. In my PhD, in close collaboration with another great lab, led by Tobias Spielmann, I investigated what happens if you make a mutant parasite that cannot sequester red blood cells. Do you still get the same pathologies? What happens to the blood vessels of the host? And how does this impact the organ and, ultimately, host survival? I basically knocked out two different genes and we found that the main syndromes that are typical for malaria don’t develop, but the burden of the parasite, such as the toxic waste it produces, is still damaging to organs, so the host still dies.

In your current postdoc you’re working with trypanosomes, so I’m guessing there have been some advances in the field and you were ready to switch to ‘the other’ parasite?

Yes, when I was finishing my PhD, there was a big story from my current boss, Luísa Figueiredo, who published that trypanosomes invade the adipose tissue, which I became very interested in. But I still did my first postdoc on malaria. It was only after it that I thought I’ve kind of covered all of the different stages of this parasite, so it would be time to do something different. Especially because Plasmodium is mostly intracellular and doesn’t move, but I really like biophysics and motility, which you can do with trypanosomes. Actually, I wasn’t expecting trypanosomes to move in tissues as much as they do, nor to display such fascinating behaviour in tissues, so the first time I saw them I thought ‘Wow, this is incredible, such a wonderful parasite!’ [laughs].

As a preLighter, you’ve written a lot about advanced microscopy techniques and also image analysis. How did you get into that?

When working with Volker Heussler in Bern, he was very keen that we have intellectual independence, and at the same time that we learn everything about microscopy – so not just how to use a microscope, but also to understand how all of it works. During my time in his lab I developed a keen interest in microscopy, but when I left his lab I realized that although I’d done a lot with microscopes, image analysis was advancing equally fast, and I wasn’t upping my game at the time. So I wanted to catch up, and I’ve been doing this part on my own for a few years. preLights is huge for me, because it helps me stay up to date on what is coming out in both image analysis and microscopy.

From your preLights posts it’s also clear that open science is really important to you.

Yes, and there are several different reasons for this. A personal aspect is that I come from Mexico, where, like in many other countries, scientists often don’t have access to all the journals, which already puts them at a certain disadvantage. I saw the same working in Brazil, Uganda and Malaysia. I think if we all had the same access to what is being discovered around the world, this would benefit everyone, because further ideas wouldn’t only come from those who can access the research.

One of my favourite examples of open science comes from Manu Prakash; he has referred to his Foldscope idea, along with all the other low-cost microscopes he and his group have designed, as ‘democratizing science’, which I totally agree with [see Mariana’s preLights on Manu Prakash’s work here and here]. When I think back to the time I used to teach in rural Mexico, I can see how this could be life-changing for someone – it’s very different to show something on a PowerPoint slide than having a kid see the real thing!

And then another aspect of open science is the idea of communicating to the public, who should be able to understand what we do as scientists. I was so happy to see a comment on Twitter for one of my highlights, mentioning that it was easy for non-experts to understand.

Finally, an important part of open science is facilitating feedback. One of the first preprints I highlighted was from Uri Manor, who had an enormous thread on Twitter, and many people were also giving critical comments about the work – and this is how it should be. I think that the more the entire community participates in the review process, the better.

“I think that the more the entire community participates in the review process, the better.”

What was the main reason you joined preLights?

There are hundreds of preprints coming out each week, and I always see a lot of them that look interesting, but never find the time to read them all. The first time I came across preLights was through Twitter, when I read someone’s post that was a succinct and really great highlight. I thought this is fantastic and that preLights is a huge service to the community, which I would like to be a part of.

And what’s your experience been like, especially regarding the interaction with authors?

I love it! I already learned a lot by making the time to read the preprints and coming up with all of the questions. But then having the opportunity to interact with authors, such as Manu Prakash, whose work I really liked already before, was fantastic! And many authors – especially Uri Manor, Pedro Ramirez, Photini Sinnis, Robert Haase and Loic Royer, and more recently Sabrina Marion and Kannan Venugopal – were very encouraging to interact with, and I learned a lot from them and their work. That being said, I do feel though that physicists and image analysists are much more open in their work and preprints than biologists, which can hopefully change in the future.

What are you planning to do after your postdoc?

I haven’t decided yet – I like too many things. Sometimes I want to be a PI to be able to answer my own questions and have full intellectual freedom. On the other hand, since I really like imaging and image analysis, and more and more institutes are creating sophisticated bioimaging platforms, I could imagine myself working at a core facility. Another option is becoming an editor; I like reading, writing and being up to date, and the best part about that job is that it allows you to read papers with all the scientific advances. And finally I’ve also been thinking about medical school and joining Médecins Sans Frontières – this comes back to what I was saying about my experience during my master’s degree and that I like seeing the real picture of the diseases.

Finally, what might some people be surprised to find out about you?

I had this crazy idea many years ago that every year I would try to learn one new language and one new musical instrument – sometimes this has happened and sometimes not. I speak Spanish, English, Portuguese, a bit of German, a bit of Russian, a bit of Greek and a bit of Italian. In terms of instruments, I can play the violin, viola, guitar, drums and a bit of piano. Another thing is that I am somewhat addicted to endurance sports; they make me feel alive, therefore the more challenging, the better!