preLights webinar with Jessica Polka: Commenting on preprints

21 May 2020

We recently started an internal webinar series for the preLights community to discuss topics such as effective scientific writing, new developments in preprints, innovations in publishing and peer review, or science outreach. For our second webinar we were honoured to have Jessica Polka, Executive Director of ASAPbio, join us as a guest speaker. Jessica gave a thought-provoking presentation and lead a discussion on how commentary and peer review are influencing preprinting.

After a brief overview of the preprint landscape, Jessica asked us what we thought about the emergence of new preprint servers. A concern brought up was the question of sustainability – if a newly launched server had to close down in a few years’ time, would there be preprints lost? We learned about a new directory of preprint server practices created by ASAPbio that includes information on which servers have a preservation plan. Fortunately, there are many that do permanent archiving of some kind, and this should be an important aspect for researchers when choosing the platform to post their work. Another issue discussed was the discoverability of preprints – and how this might become more challenging with the appearance of new servers. An important development in this area has been the indexing of preprints from various servers on Europe PMC (moreover, Europe PMC also links to sites that review preprints, such as preLights).

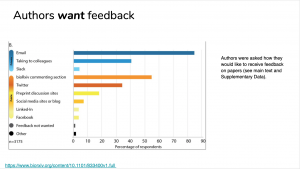

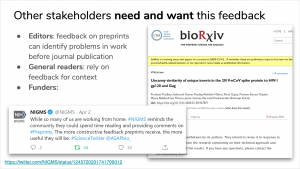

We then moved on to discuss commenting on preprints, the main focus of the webinar. A survey conducted by bioRxiv found that while most authors posting a preprint would like feedback, the percentage of authors wanting private feedback exceeds the percentage wanting feedback posted publicly. Jessica pointed out all sorts of questions this raises: if you are making a public disclosure as an author, is it reasonable to have this sort of attitude? Or by posting, are you kind of signing up for public commentary and criticism? Especially in recent times with the ongoing pandemic and preprints being in the spotlight like never before, a number of examples have shown the value of comments and how they serve the needs of the community, as well as increase trust in preprints. In fact, stakeholders have explicitly asked researchers to give comments and feedback on preprints. Therefore, the question that needs to be asked is when do the needs of the community overstep the wishes of the individual author?

Slides from Jessica’s talk. View the full presentation here

After sharing these thoughts and questions, Jessica asked us ‘Is it important for authors to signify they are receptive to feedback publicly? Or is it more important that there be an expectation for public commentary?’. People seemed to lean more towards the idea that you should be prepared to receive public feedback if you put out something publicly. However, in some cases it can be useful if authors state their intentions about the preprint they post, for example if they are sharing a dataset or resource but don’t actually plan to submit the manuscript to a journal.

The issue of public commentary is tied closely together with the issue of providing criticism in a constructive way. If this would be more common, perhaps researchers might be less concerned about potential negative effects posting a critical comment could have on their careers. In terms of platforms that work well for public comments, one preLighter noted how Twitter has become a great venue for commenting on preprints; for example, authors often summarise the main findings of their preprints in threads, which invites feedback and can lead to lively discussions.

Finally, after briefly touching on the question of whether journals should consider community feedback when making editorial decisions, we ended on a more philosophical note. bioRxiv recently changed its disclaimer to ‘This article is a preprint and has not been certified by peer review’, but at what point do we consider an article certified? There can be different degrees and qualities of certification, for example having a study published in a highly selective journal signals a different level of certification compared to publishing in a journal that does not consider perceived impact important for acceptance. And just by the very nature of how science works, it is fair to say that studies get certified multiple times – after all, there are papers that initially weren’t received well by the community, but have later shaped the thinking of a whole field.