The cold tolerance of an adult winter-active stonefly: How Allocapnia pygmaea (Plecoptera: Capniidae) avoids freezing in Nova Scotian winters

Posted on: 6 October 2025 , updated on: 7 October 2025

Preprint posted on 7 August 2025

Being active when everyone else is asleep: why the stonefly Allocapnia pygmaea survives subzero temperatures

Selected by Stefan Friedrich WirthA drastic change in seasons always presents living organisms with a challenge. They must succeed in surviving crucially different living conditions during cold winters. In arthropods, this is usually achieved by a diapause overwintering in the form of a juvenile stage that is particularly protected, such as pupa or egg.

Some stoneflies (Plecoptera, Neoptera) prefer colder environments. Winter-active stoneflies undergo their adult molt during the cold season and subsequently mate. Before the study highlighted here,not much was known about the lowest subzero temperature at which stoneflies die due to the freezing of their body fluids (supercooling point, SCP) and the biochemical basis for this cold tolerance which revolves around so-called cryoprotectants. Cryoprotectants in insects (like trehalose, glucose, proline or glycerol) normally accumulate in the insect’s body during or before cold spells and thereby shift the SCP downwards.

In their preprint, Jona Lopez Pedersen and team (2025) investigate fundamental parameters for understanding this cold tolerance in adults of Allocapnia pygmaea (Fig. 1)

Figure 1: Small winter stonefly Allocapnia pygmaea by Bob Henricks, 2013, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/deed.en

Main Methods

A. pygmaea is native to North America. Known for its sensitivity to environmental changes (Bouchard Jr. et al. 2009), it is a suitable ecological indicator organism, giving fundamental research about it even an applied relevance. Specimens were collected in Antigonish, Nova Scotia (Canada).Experiments to determine the SCP partly followed approaches already described in the literature and the cryoprotectants identification was performed via spectrophotometry.

Main Findings

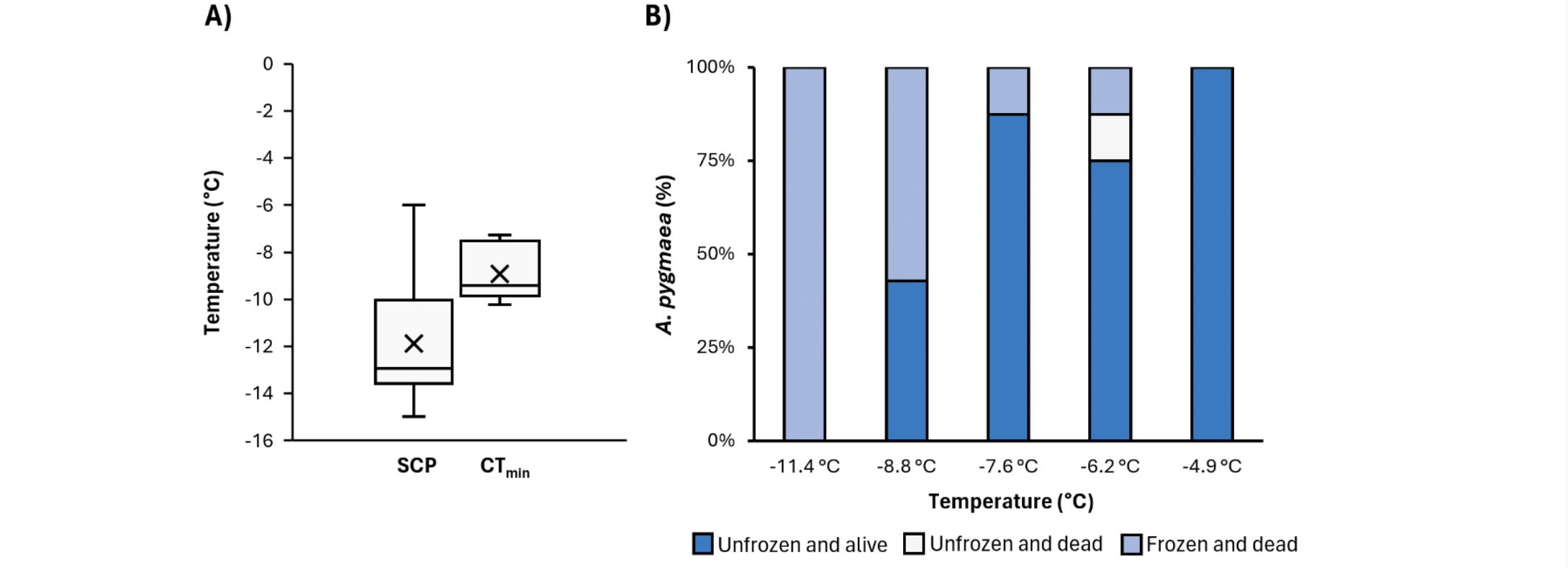

- The authors determined that the stonefly species, A. pygmaea, is cold-tolerant and freeze-avoidant (Fig. 2).

- The lowest temperature the stoneflies could survive was on average -11.9 °C.

- Until the supercooling point (SCP) was reached, a majority of stoneflies (6 of 8) remained active and retained their neuromuscular activity. A lower rate of activity began on average at -8.9 °C. Whether an individual was active or no longer active could be determined by an upright body position or by observing movements.

- Cold tolerance is often due to the accumulation of cryoprotectants. Spectrophotometric assays showed that myo-inositol was present in the highest concentration being 3-fold higher than other cryoprotectants. Glycerol was the second most abundant component, while trehalose, glucose, and proline had the lowest concentrations that were measured. In stoneflies subjected to a cold shock and then returned to higher temperatures, myo-inositol concentrations had decreased and did not stay accumulated in response to the brief, but intense cold.

Figure 2: Cold tolerance of Allocapnia pygmaea collected in Canada in spring 2023 and 2024. (A) Critical thermal minimum (CTmin) and supercooling point (SCP). The middle lines indicate the median while the top shows the first quartile and the bottom represents the third. X represents the mean. (B) Survival proportion after 1 hour exposure to one of five low temperatures. Stoneflies were categorized on whether they remained supercooled or froze during the temperature experience, and whether they survived or died within 24 hours after the treatment. This figure is part of the preprint by Jona Lopez Pedersen et al. (2025) and is licensed under the Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Why I highlight this preprint

From an evolutionary perspective, insects that are active in winter possess special adaptations to survive extreme adverse living conditions. These are primarily adaptations to escape competitive pressure from other species in the warmer season. However, the underlying biological strategies and biochemical processes used to survive harsh winters differ between species of different insect taxa. It is important to conduct in-depth studies on individual species for a fundamental ecological and evolutionary biological understandingof cold tolerance in insects, as done in this study. This kind of study is still rather rare, hence why I highlight it here.

There are various life strategies that allow an insect being active in winter. This study highlights one of them,which is of interest from an ecological, climatological and evolutionary point of view. A. pygmaea is cold-tolerant and freeze-avoidant, thus cannot survive freezing, a lifestyle which must be distinguished from the different life strategies found in other cold tolerant insects, namely those which survive freezing.

I found it particularly interesting that the animals studied did not, as one might expect, become increasingly inactive with increasing cold, despite measured limits of reduced activity (–8.9 °C), but that the various physiological and biochemical adaptations enabledactivity until the lethal minimum temperature was reached.

Future Perspectives

The exact mechanism underlying cryoprotectants’ effects has not been well studied. This is especially true in the case of myo-inositol, because it is a rather rare component found in a cold-tolerant insects. The second most common active compound discovered in the species studied here is glycerol, which is also known from other cold-tolerant insects. The authors report literature evidence that glycerol can act as a source of ATP to, for example, provide enough energy to safely reach locations with warmer microclimates, if necessary.

In general, future studies should contribute to the further understanding of the functional biochemistry of the identified cryoprotectants supporting cold tolerance in insects. This is also desirable because, according to the authors, species such as A. pygmaea, being a “bioindicative and climate-sensitive species,” might be an ecological and climatological indicator for environmental changes, for example due to global warming. Also, the role of polyols, as known cryoprotectants in other insects, such as threitol, sorbitol or ribitol, deserve (also according to the authors) further investigation in stoneflies, such as A. pygmaea.

Questions to the authors

- The authors mention in their discussion that data on the cold tolerance of nymphs are not yet available, but they suggest that the underlying cold tolerance mechanisms in nymphs differ from those in adults. I would be generally interested to know why the authors suggest different mechanisms in nymphs. In this context, I would like to ask, whether it is expected that at least the older nymph stages possess similar cold adaptation mechanisms to adults, since the adult development of non-holometabolous insects occurs gradually.

Answer: In stoneflies, nymphs are aquatic, but adults are terrestrial, which likely requires different approaches to dealing with the cold. For example, water temperatures rarely decrease below 0°C, and nymphs may therefore not need to decrease their SCP to be freeze-avoidant. However, on land, air temperatures can decrease well below 0°C, and freeze avoidance in adults is therefore an important strategy. Another species of stonefly (the Arctic stonefly, Nemoura arctica) has freeze-tolerant nymphs and the ability to survive being encased in ice (Walters Jr. et al. 2009), but the adult cold tolerance of this species has not been studied.

- Is it known whether there are certain subzero temperatures at which the animals preferentially exhibit mating behavior in laboratory conditions or in the field? And according to the authors’ assessment: can this occur at any time, as long as the temperature still permits activity?

Answer: We are not aware of any studies that examine the effect of temperature on the ability of stoneflies to mate. It is important to note that our measurements of activity were based on locomotion (moving) only. While locomotion is likely required for mating, there may be other aspects of mating biology that are affected by temperature differently from simple movement.

- Are there general hypotheses about how the trait cold tolerance might be distributed in the phylogenetic tree of stoneflies? For example, did the stem species of all Plecoptera (or in case of a paraphyly of the Plecoptera, their last common ancestor) exhibit a tendency toward colder habitats? Could cold tolerance therefore be an older trait than winter activity? And did winter activity, whether freeze-avoiding or freeze-tolerant, evolve once or several times independently within stoneflies? Does myo-inositol as a putatively rather unusual cryoprotectant possibly indicate independently evolved cold resistance in A. pygmaea?

Answer: This is a tricky question to answer, partly because there isn’t much cold tolerance work on stoneflies. In addition, cold tolerance is a complex trait, and there are not many studies on its evolution. If considering insects in general, there is good evidence that freeze tolerance has likely evolved multiple times (Sinclair et al., 2003; Toxopeus and Sinclair 2018). Winter activity in cold climates like Canada is fairly rare in insects (although common in spiders!), so it would be parsimonious to suggest winter activity has evolved multiple times within insects as well.

References

Bouchard Jr., R.W., Schuetz, B.E., Ferrington Jr., L.C., and Kells, S. A. 2009. Cold hardiness in the adults of two winter stonefly species: Allocapnia granulata(Claassen, 1924) and A. pygmaea (Burmeister, 1839) (Plecoptera: Capniidae). Aquatic Insects, 31: 145-155. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650420902776690.

Sinclair, B.J., Addo-Bediako, A., and Chown, S.L. 2003. Climatic variability and the evolution of insect freeze tolerance. Biological Reviews. 78: 181-195. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1464793102006024

Toxopeus, J. and Sinclair, B.J. 2018. Mechanisms underlying insect freeze tolerance. Biological Reviews. 93: 1891-1914. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12425

Walters Jr, K.R., Sformo, T., and Barnes, B.M. 2009. Freeze tolerance in an arctic Alaska stonefly. Journal of Experimental Biology. 212: 305-312. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.020701

Walters Jr, K.R., Sformo, T., and Barnes, B.M. 2009. Freeze tolerance in an arctic Alaska stonefly. Journal of Experimental Biology. 212: 305-312. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.020701

doi: https://doi.org/10.1242/prelights.41572

Read preprintSign up to customise the site to your preferences and to receive alerts

Register hereAlso in the ecology category:

Resilience to cardiac aging in Greenland shark Somniosus microcephalus

Theodora Stougiannou

Cannibalism as a mechanism to offset reproductive costs in three-spined sticklebacks

Tina Nguyen

Trade-offs between surviving and thriving: A careful balance of physiological limitations and reproductive effort under thermal stress

Tshepiso Majelantle

Also in the zoology category:

Resilience to cardiac aging in Greenland shark Somniosus microcephalus

Theodora Stougiannou

DNA Specimen Preservation using DESS and DNA Extraction in Museum Collections: A Case Study Report

Daniel Fernando Reyes Enríquez, Marcus Oliveira

Morphological variations in external genitalia do not explain the interspecific reproductive isolation in Nasonia species complex (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae)

Stefan Friedrich Wirth

preLists in the ecology category:

SciELO preprints – From 2025 onwards

SciELO has become a cornerstone of open, multilingual scholarly communication across Latin America. Its preprint server, SciELO preprints, is expanding the global reach of preprinted research from the region (for more information, see our interview with Carolina Tanigushi). This preList brings together biological, English language SciELO preprints to help readers discover emerging work from the Global South. By highlighting these preprints in one place, we aim to support visibility, encourage early feedback, and showcase the vibrant research communities contributing to SciELO’s open science ecosystem.

| List by | Carolina Tanigushi |

November in preprints – DevBio & Stem cell biology

preLighters with expertise across developmental and stem cell biology have nominated a few developmental and stem cell biology (and related) preprints posted in November they’re excited about and explain in a single paragraph why. Concise preprint highlights, prepared by the preLighter community – a quick way to spot upcoming trends, new methods and fresh ideas.

| List by | Aline Grata et al. |

Biologists @ 100 conference preList

This preList aims to capture all preprints being discussed at the Biologists @100 conference in Liverpool, UK, either as part of the poster sessions or the (flash/short/full-length) talks.

| List by | Reinier Prosee, Jonathan Townson |

preLights peer support – preprints of interest

This is a preprint repository to organise the preprints and preLights covered through the 'preLights peer support' initiative.

| List by | preLights peer support |

EMBO | EMBL Symposium: The organism and its environment

This preList contains preprints discussed during the 'EMBO | EMBL Symposium: The organism and its environment', organised at EMBL Heidelberg, Germany (May 2023).

| List by | Girish Kale |

Bats

A list of preprints dealing with the ecology, evolution and behavior of bats

| List by | Baheerathan Murugavel |

Also in the zoology category:

SciELO preprints – From 2025 onwards

SciELO has become a cornerstone of open, multilingual scholarly communication across Latin America. Its preprint server, SciELO preprints, is expanding the global reach of preprinted research from the region (for more information, see our interview with Carolina Tanigushi). This preList brings together biological, English language SciELO preprints to help readers discover emerging work from the Global South. By highlighting these preprints in one place, we aim to support visibility, encourage early feedback, and showcase the vibrant research communities contributing to SciELO’s open science ecosystem.

| List by | Carolina Tanigushi |

Biologists @ 100 conference preList

This preList aims to capture all preprints being discussed at the Biologists @100 conference in Liverpool, UK, either as part of the poster sessions or the (flash/short/full-length) talks.

| List by | Reinier Prosee, Jonathan Townson |

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)