Meet the preLighters: an interview with Martin Balcerowicz

20 March 2019

Martin Balcerowicz is an EMBO postdoctoral fellow at the Sainsbury Laboratory, University of Cambridge, in the lab of Phil Wigge. He studies temperature sensing in plants and the interplay between light and temperature signaling. We caught up with Martin to discuss his research, preprints and preLights.

How did you get into biology and plants?

Biology was something I was always interested in at school; I became fascinated by how you can go all the way from understanding molecules to organisms to how groups of organisms behave.

Getting into plant biology was a slight accident – as an undergraduate I didn’t really like the botany courses, where we were basically doing microscopy and drawing over and over again each week, and this shaped my initial idea of plant science. But when choosing my advanced courses, I didn’t manage to get into one of them (genetics), so I took up molecular plant physiology instead. This is basically how I got to know that you can do many cool things with plants – including molecular biology, biochemistry and genetics – and I pretty much stuck with plants since then.

Already in the beginning of your research career, you travelled to the other side of the world for science.

Yes, I started as a student assistant in Ute Hoecker’s lab in Cologne but for my diploma thesis I wanted to travel abroad. Ute established a connection with Jo Putterill in New Zealand, who works on the regulation of flowering in Medicago, so this was my first proper venture into plant science. Afterwards, I came back and joined Ute’s lab as a PhD student, working on Arabidopsis, the classical pet of the plant scientist.

What was the question you were trying to answer during your PhD research?

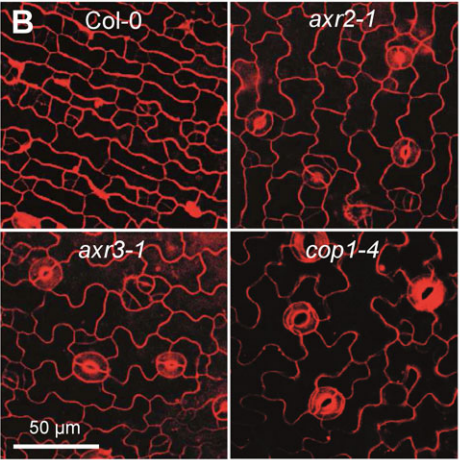

I actually had multiple projects. My main project dealt with light signaling and trying to understand how plants perceive light. We worked on a repressor complex and wanted to figure out how light influences its activity. I started my other project about a year into my PhD, which dealt with one of the most famous plant hormones, auxin. We showed that auxin represses the development of stomata in darkness, and this publication was one of three that came out roughly at the same time and demonstrated the role of auxin in stomata development for the first time.

And now, what are you working on in your current postdoc lab?

The main question in the Wigge lab is how plants perceive and respond to temperature. One aspect that is not well understood is the response to ambient temperature (for example the plant’s developmental response to warm summer days, rather than to extra hot conditions which result in heat stress).

A lot of research so far has focussed on constant temperature environments. I am particularly interested in how plants adapt to cycling temperatures and try to understand how they respond as the temperature increases during the day. We have identified several genes that play a role in this process by using a combination of genetics and genomics approaches.

Many of the genes that are regulated by temperature are also regulated by light, so in another project I am investigating the crosstalk between these two signals.

Could you tell us your favourite aspect of research?

Experiments – but only if they work! [laughs]

In the bigger picture, I would agree with many who say that finding something novel is what you really want as a scientist, and this gives the satisfaction that drives me.

Moving to preprints, what’s your experience and take on them?

They come up in journal clubs and paper discussions in the lab more and more often, and I think they are being picked up more and more in the plant sciences as well.

With preprints, the dissemination of results is just much quicker, so this is a pretty cool way to move science forward. Also, it’s common to see people struggling to get their paper out, often for a year or more, which can become damaging for your career. Preprints are now more valued and considered some form of publication – not peer-reviewed obviously, but still your work is out there and can be read and scrutinised by any person who’s interested.

When publishing my previous papers, preprints were still new to us, so we didn’t really give it much thought, but nowadays we would definitely discuss whether to go preprint when submitting a paper. Of course, every major author has to agree to do it and that might be tricky in large collaborative projects.

What was your motivation to join preLights?

I was already looking a bit into what I could do in terms of science communication. In contrast to many people, I actually really like writing, it doesn’t necessarily feel like work to me and it’s something I can always do in the evenings.

I also think it’s important to promote preprints; even though they are getting widely recognized, we are not yet at the point where they are accepted by all journals and major funding bodies.

Finally, another thing that got me into preLighting is that I feel plants are often a bit overlooked, a fact that is sometimes referred to as plant blindness. But compared to other fields, many techniques are really similar and there are many fundamental discoveries that have been made in plants. With my preLights I hope to make a small contribution to promote plant science to a wider audience.

“Another thing that got me into preLighting is that I feel plants are often a bit overlooked […]. With my preLights I hope to make a small contribution to promote plant science to a wider audience.”

Do you already have plans for after the postdoc?

It’s pretty much up in the air. I might try to make the transition to become a PI, but I think the step from postdoc to junior PI is probably the most difficult in academia. I could also see myself in a job in industry or science communication instead.

Finally, what would people be surprised to find out about you?

I’m a really big football fan, cheering for my hometown Cologne. Their performance usually isn’t that great, so I always say that I got my grey hairs from worrying about them. Nevertheless, when I make my visits to Germany, I try to catch their matches.