Meet the preLighters: an interview with Teresa Rayon

15 July 2019

Teresa Rayon is a postdoctoral researcher in James Briscoe’s lab at the Francis Crick Institute. Here, she studies how time is measured during development. We met Teresa at her institute to talk about her passion for science, her outreach activities which involve running a science podcast and preLights.

Let’s start with the very beginning, how did you get into biology?

When I was a kid, in the summer we would go to Asturias (North of Spain) to visit my two aunts, Mari Carmen who is a biology teacher and Chelo who is a haematologist. I have very good memories from those summers; Chelo sometimes had to work of course, so she would take me to her actual lab, where we would do things like blood tests – and I remember that being super fun! Therefore, I often associate the lab with my summers and happiness.

With Mari Carmen and my cousin, we would spend a lot of time out in the parks and the mountains. She would show us the huge diversity of trees and all the possible animals we could find – we would also pick things up and bring them back home. So maybe it’s around this time when I first thought doing something like this for a living would be cool, and I think it’s also where my passion for biology comes from.

You then did your biology studies in Spain.

Yes, I studied biology at the Autonomous University of Madrid. But then for my Masters project, I went to Aarhus in Denmark with an Erasmus fellowship. By then I already knew that my favourite part of biology was developmental biology, so I actually decided to go there because I found a group studying development in mouse. I then went back to Spain for a PhD and joined Miguel Manzanares’s lab in Madrid, because I really liked his evo-devo approach. At that time he was using both mouse and chick models to study the evolutionary novelty of pluripotency, and how the gene-regulatory networks controlling it get assembled in mammals.

And specifically, what was the question you were working on?

My project was on the first cell fate decision in the mammalian embryo, which is basically whether to become the trophectoderm (which gives rise to the placenta) or the inner cell mass (which forms the embryo). I wanted to understand how Cdx2, which is the key factor for the trophectoderm, is regulated. I was first looking into whether its enhancer element that we characterized would be responsive to Hippo signalling, but it turned out to be more complicated than that. We were lucky enough to find that the Notch signalling pathway was partnering with Hippo to regulate Cdx2. In the end, the main finding of my project was that Notch has an earlier than anticipated function in early mouse development.

Following your PhD, why did you choose The Crick and James Briscoe’s lab for your postdoc?

Because I love London [laughs]. But the other reason was that I thought it made sense for me to change systems. What is nice about blastocyst development is that the small number of cells are simple to follow and image. But it lacks a bit the complexity, and I really wanted to go to a place where I could increase the complexity and study development in a more quantitative way. So joining James Briscoe’s lab was a really good choice, and it allowed me to work in a multidisciplinary environment, and broaden my knowledge by interacting with people who do things differently than me.

What are you studying now in your postdoc project?

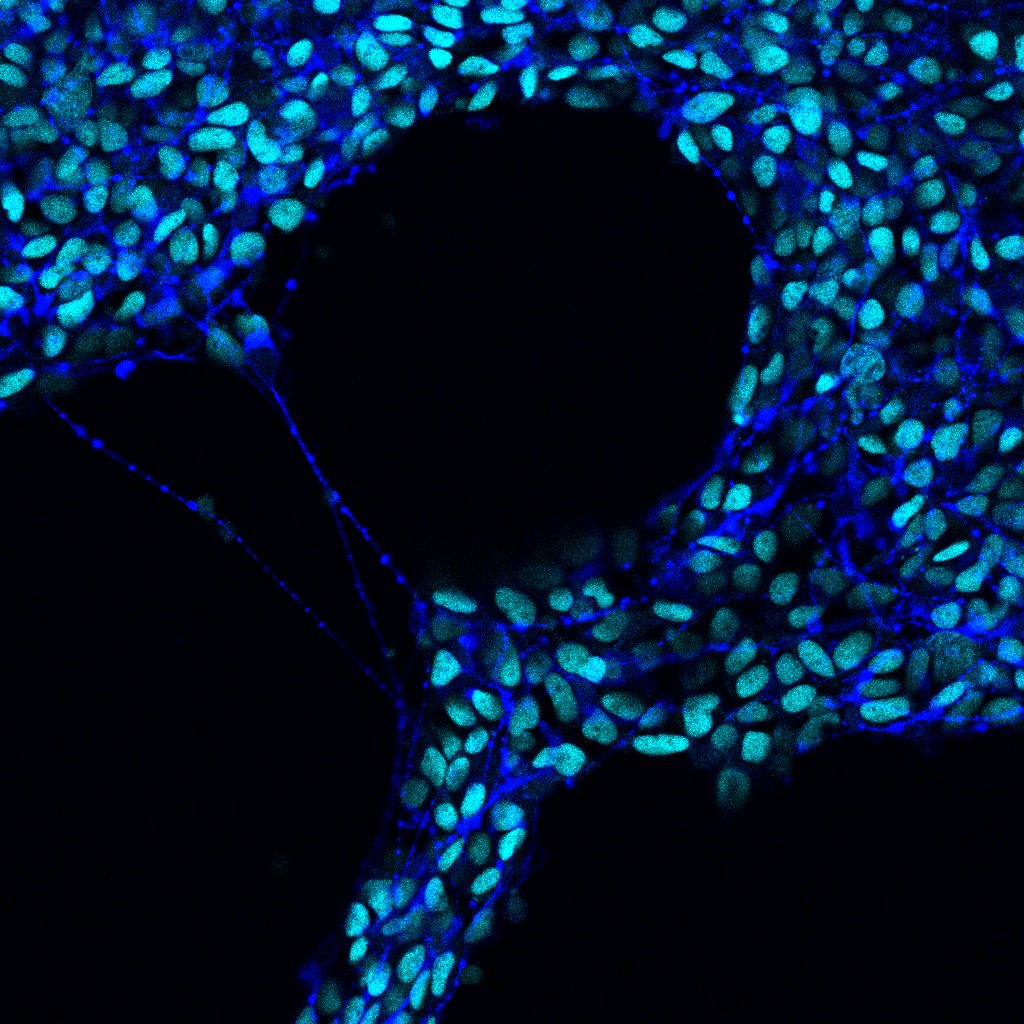

I’m trying to understand temporal control during development. My strategy is to study the same highly conserved differentiation process and look for properties among the species that operate on different time scales. To be more specific, I am studying the differentiation of motor neurons from neural progenitors in mouse and human. Because obtaining human material is complicated, I have developed an in vitro model from human stem cells which is homologous to the one we use in the mouse; this allows me to precisely dissect the temporal scaling differences and ask what processes determine the ‘speed’ of differentiation.

You were involved in a paper that just came out in the recent Development single cell special issue. I was happy to see its preprint version earlier – is this a common thing to do in the lab? And why do you think it’s useful?

Yes, preprints are a common thing in the Briscoe lab. The idea is that the moment you have your story ready and you are happy with it and want to share it, the most rapid way to do that is publishing a preprint. I think apart from the well-known advantages, it’s great for the community to see how you think about your own work without any filtering or peer-review. The other aspect that was very useful in our case was that at the time we posted it, Andreas was looking for positions, and having a preprint on your CV really does count.

You’ve been part of the preLights team since the very beginning, why did you decide to join?

I was invited by James [the recruitment of the first group of preLighters was invitation-based], he asked me if I was interested, and for me the first obvious reason to join was to improve my writing. And I really think I’ve learned a lot since joining. But the thing I like most about preLights is that you can comment on the work at the time when the authors are ready to share it with the community, and you do it in a way that is completely transparent and open to everyone. Rather than being a tough ‘reviewer 3’ asking for all those horrendous experiments, you are someone who is enjoying the work in the state that the authors think is readable and shareable.

How have your interactions with preprint authors been so far?

I’ve had some super nice interactions with preprint authors. The best example is probably my first preLight; when I contacted them they were really nice and answered all of my questions. What was really cool is that this work was published in eLife, where you can see the whole peer review process with the comments of the referees and the authors. I saw that one of the referees asked the same questions as I did in the preLight, and the authors referred to their discussion with me and cited the preLight. I loved the fact that even though this was the very first time that people started ‘preLighting’ things, the authors could pick it up and make use of it. If I were to have a box where I put all the happiest moments I had in science, this would be one of them!

“[…] I loved the fact that even though this was the very first time that people started ‘preLighting’ things, the authors could pick it up and make use of it. If I were to have a box where I put all the happiest moments I had in science, this would be one of them!”

Another nice experience was a joint preLight I wrote together with Sarah Bowling. When I saw the preprint I knew it fit really well with her background, but I was also really interested in the topic, so I contacted her asking if she would like to write about it together. I sent her a draft about some of the things we should touch, and she then picked it up from there. I was a bit sad that we didn’t get an author’s response, but I think it’s often because authors fear that commenting might be bad for the revision of their paper, and not because they wouldn’t want to talk to you about their work. But in the most recent preLight I wrote, the interaction with Miki [preprint author] was great, since she gave feedback on the preLight and also answered my questions.

As a preLighter, you have given talks about this initiative at meetings. Could you tell the readers about this?

Yes, there was a meetup organized by the Open Access team at the Francis Crick Institute with the theme preprints and science news- how can they co-exist? Here I talked about what we do as preLighters and how we advocate for open science. It was exciting because the talk was followed by a real panel discussion.

I also presented about preLights at the STM week last December. It was a good experience, because it was the first talk I gave which was not strictly science-oriented, so I had to present in a way that is a bit different to how I usually communicate to scientists. It was really interesting to be in the session about diversity and open access, and I enjoyed the interactions; for example Sam Hindle was there from PREreview, and I met many people who are on the other side of science, for example journal editors.

Your passion for communicating science is also evident from the Spanish science podcast you run. How did you get involved with “En Fase Experimental” and what sort of topics do you cover?

First of all, if you’re Spanish or want to learn Spanish, please listen to it [laughs].

I really like radio broadcasting and used to do it in Spain, but that was about music. When I came to London I thought it would make sense to start a podcast about science. The Society of Spanish Researchers in the United Kingdom was looking for people for a new science podcast, so I just applied.

‘EFEX’ is run by a team of six people, we invite scientists or people in areas related to science to talk about a topic that researchers might find interesting, such as career building, open access, Nobel prizes, academic Twitter and so on. We also make a really strong case for women in science and have a separate section about this – we choose a topic and select a women scientist who has made a significant contribution to that field.

An interesting story is when I invited Oscar Marín, it happened to be the week for women in science, so I asked him who his favourite women scientist is. He mentioned his wife (Beatriz Rico) and Angela Nieto [Who has just been awarded the Spanish National Research Prize], and told us that he admires Angela’s hard work. The following year I interviewed Angela during the women in science week and could link back to the previous year’s interview.

As an advocate for women in science, what do you think would be the most important thing that requires change?

I think one of the major problems is the cultural conception of who is a successful scientist. People often think that the very self-confident people are better scientists, whereas that’s not always the case, and it comes down to education. So this problem is not strictly about gender, but more about diversity – you can be a good scientist in many different ways.

What are your future plans in science?

I would like to keep doing science as long as I can and not drop out. It’s obviously a very competitive career, so now I’m just aiming to do it the best way I can and as long as I can. It feels like the only way to stay long-term in academic research is becoming a PI, so that’s my future plan.

Finally, what would people be surprised to find out about you?

I collect analog cameras and also have polaroids – you actually wouldn’t imagine the number of cameras I have! I like them because they work the old way – you cannot just repeat any photo. In 2012 I did a trip to Africa visiting many countries, I think I took 4 or 5 of my cameras on that journey.