Meet the preLighters: João Mello-Vieria

15 September 2021

João Mello-Vieira joined preLights earlier this year, and has written many preLights posts on parasitology. Recently he has moved away from academic research into science writing and communication. We caught up with Joao to learn more about his new role and how preLights helped him decide to move into a writing job.

What inspired your initial interest in science?

I became interested in a career in science in high school. I remember being in a biology class talking about cells and proteins, and metabolism really stuck with me. Glycolysis, the Krebs cycle – I was just amazed that we have these little machines inside us that can convert one molecule into another and create pipelines and the energy we need. I was really amazed at how mechanical it all seemed – like the ‘human machine’ that used to be talked about. I was interested in learning more and trying to decode these mechanisms that we live by, and it was the first time that I really knew what I wanted to do, so I started specialising in science towards the end of high school and this led to me pursuing my undergraduate degree in biochemistry.

Your Twitter bio says you have a past life as a parasitologist! What did this past life involve?

The idea of a past life came from when I was doing my PhD. We had lots of colleagues that came from different labs, and they always used to refer to the labs they used to work in as their ‘past lives’, so I thought it was funny to put that as my bio! I did my PhD in a parasitology lab, and my research focused on malaria – specifically Plasmodium, the parasite which is the causative agent of malaria. The focus of the lab is the fundamental biology of the parasite, particularly the liver stage of the malaria parasite lifecycle. The parasite is transmitted into humans from mosquitos, and initially goes to the liver, before entering the blood. It’s during the blood stage of the infection where people get sick and the disease can be fatal. In the lab we were focusing on the liver stage, before symptoms arise.

My project was about a protein called Exported Protein 2 (EXP2) and its function during the delivery stage of the Plasmodium lifecycle. I used conditional knockouts to see what role the protein played in the liver stage – expecting that the parasite would establish in the liver but not be able to grow – but instead we saw that the knockout parasites couldn’t even invade the hepatocyte at all. It took me about two years to convince my PhD supervisor that this was something interesting and worth focusing on!

Did you enjoy your time as a PhD student?

Being in the lab was a wonderful experience. It was a bit scary when I joined because there were only two or three other PhD students out of around 25 people! We had people from all over the world: the US, Mexico, Serbia, Cameroon. All these people from different countries with rich life stories and achievements, and I felt very small and insignificant in the middle of that, but it was incredibly interesting. Everyone was dedicated to the science and to the lab as a community and was always willing to help other people’s projects. For example, microscopes in the communal facility opened for booking at 1pm every day, so at 1pm we’d all rush to our computers and then exchange the slots between one another so we could all use the microscopes around our experiments. It was such a friendly environment; we’d go for dinner or for lunch together whenever possible. My PhD was a really fun time.

Then you moved to Spain for a postdoc – can you tell us about that?

Yes, I moved to Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Oncológicas (CNIO, The National Centre for Cancer Research in Spain) after finishing my PhD. My parasitology project was very fundamental science: cell biology heavy and, of course, parasitology heavy. I wanted to challenge myself to do something a bit broader, and perhaps with a little bit more significance and outreach potential, and there was the possibility for me to do a postdoc in a telomere lab. Telomeres are the structures at the end of chromosomes, and if they get too short (as we age) then cells can’t divide, so they need to be extended with telomerase. At the same time, as we get older, we start to lose the ability to fight off infections. I wanted to mix the concepts of ageing, telomere biology and telomere lengthening with the infectious diseases experience I’d gained in my PhD. Can we use telomere therapies to reverse some of the problems we get in ageing with infectious diseases?

How far did you get into investigating this?

I was just searching papers – I didn’t actually do any experiments to prove this! But as we get older, our immune system becomes much more inflammatory, so we respond better to infections in the sense that we create more inflammatory molecules such as TNF, interferons – everything we need to kill the bugs. The problem is that this leads to a lot of tissue damage as a result of the immune response, and as we grow older our tissues have less ability to repair themselves. That means we don’t necessarily die of the infections; we die of the response we create to the infection, which is much bigger than it would have been when we were younger.

But it was a funny thing, I was presenting this data and the experiments I’d thought about doing and I realised at one point in the lab meeting – I don’t want to do this experiment. Actually, I don’t want to do any more experiments! I was only in the postdoc for seven months, and it was during that time that I started writing for preLights, and I think that helped me understand what I wanted to do with my career. I became much more engaged with writing for preLights, and I realised I liked writing about papers more than I enjoyed thinking about and planning experiments. That was a sign that I needed to change careers.

Was thinking about a career change quite sudden?

I think I would have decided to change my career even if I hadn’t started writing for preLights – that was just what jumpstarted it! It made me realise I can do more than just do experiments and write papers. I still want to do science and be connected to science, but I want to contribute to that in a different way, and preLights helped me understand that maybe I could write and explain scientific concepts.

I was very fortunate because I’m still in touch with one of my PhD supervisors who has also changed career. She had been a postdoc for 10 years, working on malaria, before she had the opportunity to work for a company using DNA and RNA sequencing to investigate biodiversity. I think a lot of European projects are now aiming to understand large-scale biodiversity – in the ocean, in the soils – and she’s very happy leading this team now. I called her when I realised I didn’t want to do anymore experiments and asked her so many questions: Can I quit this postdoc? Is it too soon? Should I try and give it a go for longer? She helped me get my head straight to think about what I wanted to do, and that was really helpful.

Were you sad to leave the bench behind?

I was sadder about leaving the people in the lab and the lab environment than the experiments themselves. I miss lab meetings and bouncing ideas off each other to help solve a problem – I worked in labs that a great feeling of camaraderie, so I do miss that.

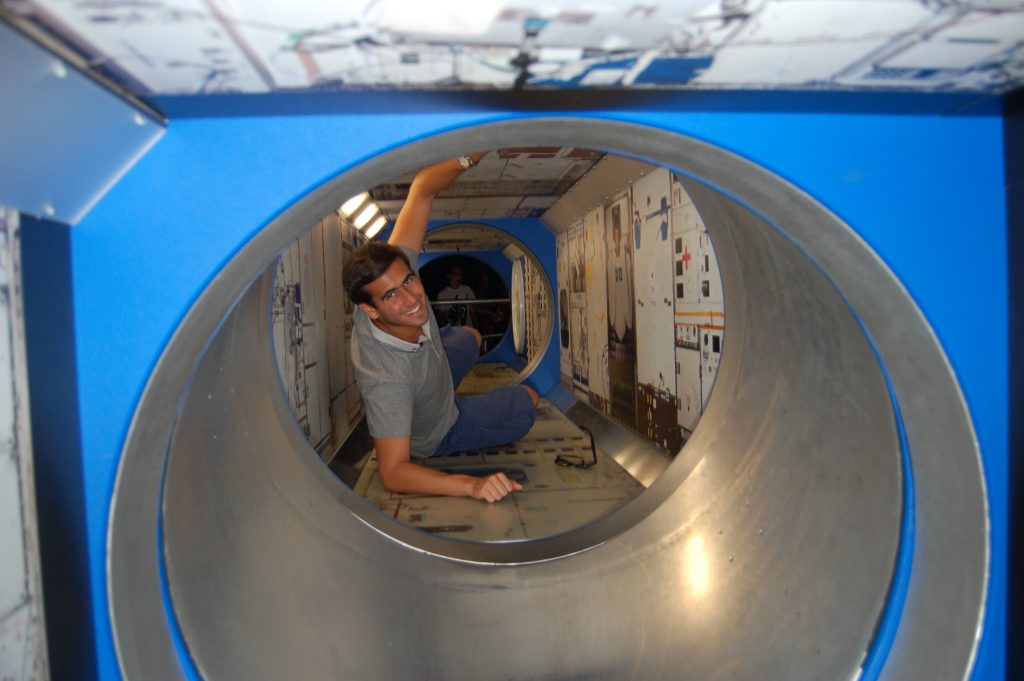

Parasitology to space science! João visiting the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, US

What does your new role look like?

I work for a Brazilian company called Publicase – the enzyme that helps you publish papers! The founder of the company (Marcia Triunfol) did her undergraduate degree in Brazil, her PhD in the US and worked as an editor for Science in the US before deciding to move back to Brazil. When she moved back, she realised there were lots of research groups in Brazil that needed help publishing papers, either by translating papers from Portuguese to English or just polishing the sentences. She knew the publishing world and was fluent in English and that’s how the company started.

The company has two branches of operation. One is that a research group sends their manuscript, either in Portuguese or in English, and we can translate or help polish sentences into a more scientific, direct style. Portuguese and Spanish have a tendency of speaking in a hard, let’s say, convoluted way, which means when we write in English we also write in a convoluted way. One thing I realised from my PhD was that learning how to write scientifically in English was quite challenging. So the company helps these Brazilian groups make their papers more straightforward. The second part of the company is giving workshops to help scientists write their paper in one month; we explain how to structure different parts of the paper and guide them through the process and give one-on-one coaching about the particularities of a specific paper. I’m really enjoying it so far.

Do you think English proficiency can be a barrier to scientists in different countries?

I think it is. First you need to know how to read English to understand papers. There’s a lot of textbooks written in Portuguese or any other language, but to be able to do a PhD you need to know how to read the papers in English. Then, once you have your data you need to present it at conferences. More than writing your paper, I think English is very important for conferences because you need to speak to people in English – to engage with people, troubleshoot a protocol, understand a technique or even understand and reply to questions. When you write your paper that’s normally with a supervisor who is likely to be proficient in English at that point in their career, but the better they are at English, the better the paper will be presented, and the better you write the paper, the better the chance of getting past the editor. That means it can be a barrier to some groups, especially if access to English classes is not so easy.

What I’ve realised from the papers I’ve received is that it doesn’t matter is the paper was written in Portuguese or English, the quality of the science is good. Even though people might not know English very well, they can still execute science at a very high level.

Are there any Portuguese language journals?

Yes I had to look these up! There are about 60 scientific magazines in Portugal and Brazil – roughly 30 in Portugal and 30 in Brazil. They cover a wide range of topics in natural sciences, psychology, and social sciences. There are even three journals that are indexed on Web of Science – two from Portugal on geography and museology and one from Brazil that publishes papers on geology. Two are in English but I think the one on museology is even published in Portuguese.

Is science writing something you see yourself staying in long term?

That’s a tough question – I don’t know. I’m having a lot of fun now, I’m really engaged in the projects that we’re doing with the workshops and in editing the papers, but I do miss the camaraderie of the lab and working with more people. There are advantages of being a freelancer, but I miss having colleagues to talk to, so let’s see what wins out in the end!

You’ve mentioned how preLights helped you move into this role, but how did you find out about preLights in the first place?

I first came into contact with preLights via Mariana de Niz and Mafalda Pimentel, who were both colleagues of mine when I was in Lisbon. During early COVID quarantine I started using Twitter more often, and I would see Mariana tweeting about cool new preprints and doing these digests of papers for the scientific community. I always loved journal clubs – I think everyone else in my labs hated journal clubs, but I would do them every week if possible – so I decided I wanted to give it a shot and start writing about preprints, where there’s a huge amount of data being published or deposited in the archives.

Do you enjoy interacting with the preprint authors?

I’ve been really lucky with the authors I’ve contacted – they’ve always replied, and always given me a bit of extra information that wasn’t in the text or in my questions, so I find that’s a really positive experience. One of the authors I contacted, Bill Sullivan, even gave us the opportunity to write about preLights for PLOS SciComm.

And to finish – what’s something surprising about you?

This related to a conversation I was having with some friends, about two or three weeks ago. We were talking about travel and I said I would rather travel somewhere with a rich history or art scene, rather than going somewhere to hike or for natural beauty. I started to think about why I prefer cities, and I think it must be because I love history and thinking about how we came to be right now. I don’t know if it’s surprising but I really like history.