Leadership in PhD (LeaP): a longitudinal leadership skill building program for underrepresented biomedical research trainees

Posted on: 24 October 2022

Preprint posted on 13 September 2022

Designing a leadership training program called LeaP for incoming PhD students

Selected by Kanika KhannaCategories: scientific communication and education

Background

It is no hidden fact that as one climbs the hierarchical ladder of the scientific workforce, one would see fewer underrepresented minorities in top leadership positions, including women, Black and Hispanic scientists. This isn’t because they don’t like science or are not competitive. Several independent studies have pointed to a number of factors – including, but not limited to – bias and discrimination in hiring and promotions, lack of adequate resources and networking opportunities and lower levels of self-confidence in securing funding and awards. Even though the number of doctorates earned by underrepresented minorities has increased (32% increase from 2006 to 2016 for African Americans and 67% for Hispanics during the same period), this has not translated into similar growth in faculty-level and senior leadership positions.

Increasing diversity in the scientific workforce is of critical importance. The authors in the preprint argue that developing leadership skills in underrepresented Ph.D. students can be a key step to promoting their self-confidence and retaining them in the academic workforce. To this end, they have developed an outline for a 4-year long program called “Leadership in Ph.D.” or LeaP to equip Ph.D. students with leadership skills needed to succeed in academia, industry and community.

Different institutes and scientific societies offer many leadership training programs, but many of them are directed toward people in already advanced career stages and/or are designed as short-term intensive workshops. LeaP aims to fill these gaps by targeting underrepresented minorities almost as soon as they start their Ph.D. programs and keeps building upon their individual leadership skills throughout the course of their PhDs.

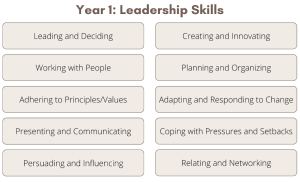

Figure 1. 10 leadership competencies that are the focus of the first year of the LeaP curriculum

Key findings

In order to evaluate the program at the end of the first year and to plan future improvements, the program directors gathered both qualitative and quantitative metrics. After each module, the participants were sent a survey to rate the effectiveness of the session, major takeaways from the session and suggestions for improvement.

About 4 or 5 students responded to each module survey and generally rated sessions positively. Survey results suggested that one-on-one coaching sessions were very effective in helping students understand their individual strengths and areas for improvement to develop their leadership styles. Students did not have a lot of input regarding future areas of improvement for sessions, but they indicated that they would like more opportunities for participation and discussion in sessions.

To gather qualitative input for the program, LeaP directors held a focus group and asked various evaluation questions regarding different sessions, group dynamics and the impact of the program. Responses were again mostly positive with some feedback regarding how discussion sessions were facilitated, having more in-person sessions and ensuring gender balance in the cohort. Some positive remarks by students that resonated were “having a cohort they could rely on throughout their Ph.D. program” and “focus on reflection and gaining great knowledge of their strengths and areas for growth”. The authors have similar evaluation metrics for their program in subsequent years that they hope to gather via periodic surveys and peer assessments.

What I like about the preprint

I wholeheartedly concur with the authors that LeaP is a step up from other leadership development opportunities in that it is a training program that runs in parallel with students’ Ph.D. programs. This sets the stage for PhD students, especially underrepresented minorities to get the requisite training, skills and confidence in leadership early on in their scientific careers. Students in a cohort get to know each other at a deeper level and this camaraderie can help them feel a sense of belonging. Moreover, the program is longitudinal and encompasses 4 years of training. This is in contrast to short-term intensive workshops and ensures that early career researchers keep learning and developing themselves on a regular and longitudinal basis. This will help students in whatever career path they decide to choose later on at the conclusion of their Ph.D. I sincerely hope such a training program can be implemented by institutes and Ph.D. programs as a part of professional development in Ph.D.

Concluding thoughts/questions for authors

The authors have elegantly laid out a blueprint of LeaP activities for the inaugural cohort in their first year. It will be exciting to follow them on their journey as they tell us about their progress in subsequent years and the potential LeaP has to make an impact on the career trajectories of underrepresented PhDs. The authors make a note that scaling LeaP effectively will take time and needs to be implemented after careful consideration and accounting for variabilities.

- Are the lesson plans and evaluation forms for the first-year LeaP curriculum available for other institutes/programs to adapt?

- At present, most of the trainees in the inaugural cohort belong to underrepresented minorities. Have the authors assessed whether their participation in LeaP has impacted their progress in Ph.D. program directly or indirectly in any way? Perhaps, any positive impacts in terms of leadership skills?

- Do LeaP students in any way think this is adding additional coursework to their PhD compared to the rest of their cohort?

- If possible, it would be useful to get demographic data (gender, ethnicity, race, etc) for the first cohort enrolled in the LeaP program.

- It will also be useful to detail the qualifications/demographics of people who facilitated sessions, discussions and one-on-one coaching. There are studies that have shown that connecting female students with women working in STEM helps them envision themselves in those roles. Perhaps a discussion about the role of discussion leaders/coaches in LeaP can help strengthen the program guidelines and potential impact.

- How do the authors plan on supporting this program long term, including rolling it out to other institutions and the financial support necessary for providing a community around this course?

- How much is this based on known pedagogy methods? How are implementation practices by students judged as a lot of curriculum relies on self-directed learning?

doi: https://doi.org/10.1242/prelights.32952

Read preprintSign up to customise the site to your preferences and to receive alerts

Register hereAlso in the scientific communication and education category:

Kosmos: An AI Scientist for Autonomous Discovery

Roberto Amadio et al.

Identifying gaps between scientific and local knowledge in climate change adaptation for northern European agriculture

Anatolii Kozlov

Spurring and Siloing: Identity Navigation in Scientific Writing Among Asian Early-Career Researchers

Jeny Jose

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)