An updated and expanded characterization of the biological sciences academic job market

Posted on: 1 October 2024 , updated on: 19 November 2024

Preprint posted on 2 August 2024

Article now published in Frontiers in Research Metrics and Analytics at http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/frma.2024.1473940

Fantastic academic jobs and how to find them 🪄

Selected by Jennifer Ann Black, Chee Kiang Ewe, Barbora Knotkova, Ryan HarrisonCategories: scientific communication and education

Updated 1 October 2024 with a spotLight by Jennifer Ann Black

This article was co-written by Reinier Prosee, the preLights Community Manager.

Background

It’s the anxiety-inducing question that all (early-career) researchers try to avoid: what is the next step? Navigating a STEM career is notoriously tricky, if not only because for every 6.3 PhD graduate there is only 1 tenure track faculty position (1). What happens as a result is that many choose to either leave academia altogether or linger in low-paying postdoctoral roles, hoping for their break into a permanent academic position.

There are many factors that influence one’s chance at securing a faculty job – but which factors lead to success are somewhat shrouded in mystery. To provide some clarity, in come the authors of this preprint: they surveyed 449 faculty applicants in the biological sciences over three hiring cycles from Fall 2019 to May 2022. In doing so, they reveal the impact of factors like gender and gender identity, among others. Not only does this study help to demystify the faculty job market, but it also empowers (early-career) researchers by allowing informed decision-making.

Key Findings

Submitting more applications is a positive predictor of a job offer

The survey showed that around 60% of respondents were successful in receiving one or more offers, with a median of 1 job offer per applicant. The authors first compared the research productivity of applicants who received at least one offer to that of all applicants:

Metrics that were NOT associated with an offer :

- Number of application cycles

- Number of peer reviewed papers (~11 papers in both groups)

- Number of first author papers (Researchers with a job offer actually had a median of 5 compared to 6 in the total group)

- Corresponding author papers (Researchers with a job offer had a median of 0 compared to 1 in the total group)

- (Co-)Principal investigator funding

Metrics that were associated with an offer:

- Number of submitted applications (Researchers with an offer submitted a median of 20 compared to 15 in the total pool)

- Citations and h-index

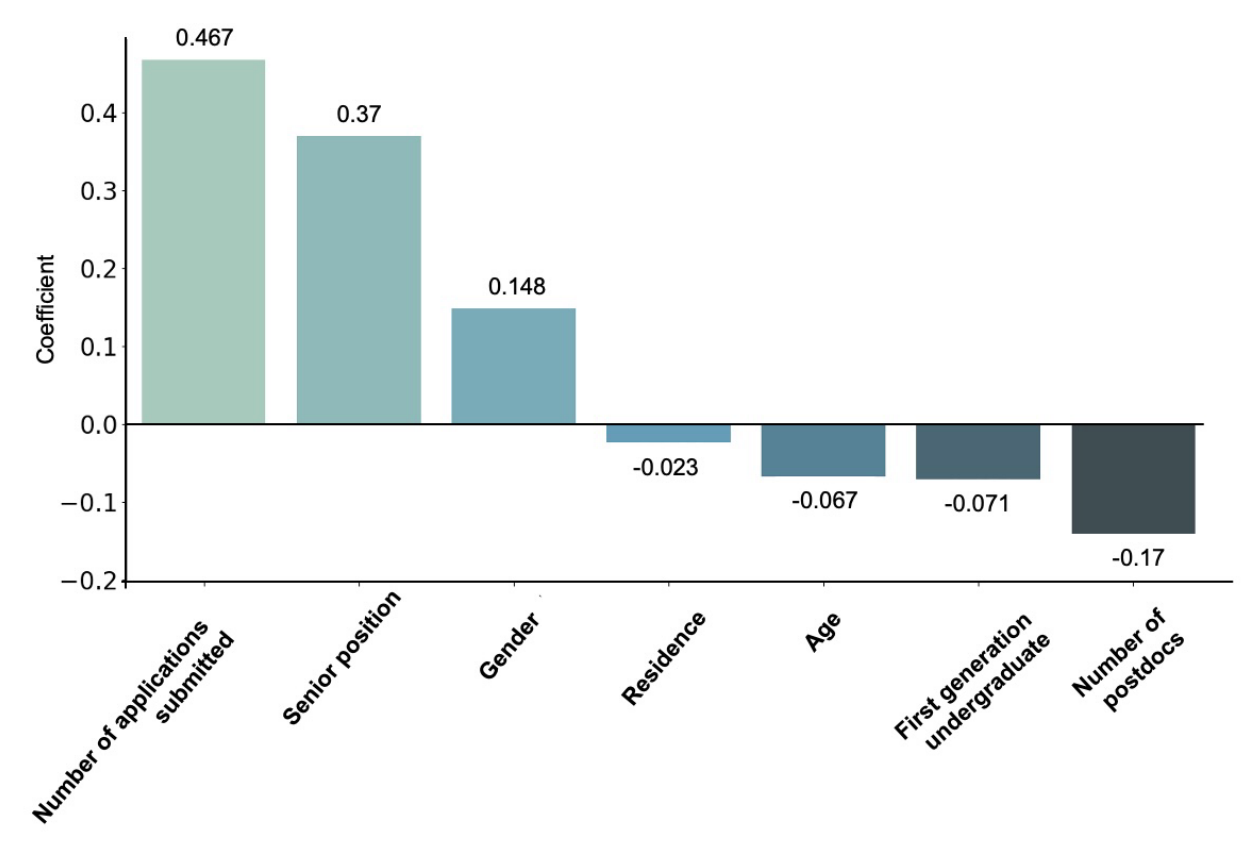

To solidify these findings, the authors modeled their data from 2019-2022 and tested for predictors of academic job offers. In agreement with the observations from their surveys, the most prominent predictor of a job offer in academia was the number of applications submitted, closely followed by having a senior position at the time of the offer. The most prominent predictor of no offers received was a higher number of PD positions at time of application.

Graph adapted from Flynn et al. showing the relationship between factors that positively and negatively correlated with receiving an offer of a faculty job.

PEER status does not correlate with receiving a job offer

The authors compared applicants from PEER (persons historically excluded because of their ethnicity or race) and non-PEER groups and found that there is no significant differences in scholarly metrics measured or overall success on the faculty job market between the two groups. The authors also found that PEERs tend to be first-gen undergraduate and graduate students. However, it is important to note that only 10% of the respondent pool met the definition for PEER status. The low number of PEER participants makes it difficult to accurately assess the experiences of PEER faculty applicants.

Women and LGB+/GNC individuals are more likely to receive job offers than men

When examining gender, including men, women and LGB+/GNC individuals, the authors found that though each group sent similar numbers of applications, women overall received more job offers. Even though women and LGB+/GNC individuals were less likely to publish in some of the well-known scientific journals (Cell, Nature or Science; CNS).

What we liked about the study

Jenn:

I really enjoyed reading this paper but as a PD with ~ 7-8 years past PhD I found it worrying to see that having more years of PD experience didn’t seem to correlate with increased chances of an academic position! I had always thought more PD experience would help. I am however glad to see that this type of information is now available for younger scientists to help guide their decisions re academia.

Barbora:

As a fresh PhD graduate, it is hard for me to estimate how achievable an academic position would be for me. I think it is great that the authors are working towards achieving some clarity in the factors that contribute to landing an academic position. I believe that it will make it easier for people like me who are at a crossroads in their academic career to decide which path to take.

Ethan:

I agree with Barbora that this study provides some transparency to the elusive academic job market. As a postdoc preparing to enter the job market, this data helps me assess my own competitiveness.

Reinier:

This work offers such a valuable resource for navigating the complex world of (biological) science. What I particularly appreciate is that the preprint authors took time alongside their own academic work to help others find their way in what can often feel like a confusing and overwhelming career path.

Ryan:

I agree that I like how the study is beginning to demystify the factors determining the success of pursuing a faculty position in biological sciences. I would be interested to read about if the authors follow this up further with a different cohort of people – e.g. with a higher percentage of people based outside of North America – to see if they get similar results as this study.

Questions for the Authors

Q: Have you explored the effect of the PI on how successful candidates were at receiving job offers?

Q: Why do you think that having more PD experience appears to correlate negatively with securing an academic position?

Q: What are best practices to get hired?

Q: Among the many findings, what surprises you the most?

Q: Some applicants without a first author paper were successful in obtaining an offer. Do successful applicants with fewer first author papers have a higher number of total peer reviewed papers than others?

References

- Ghaffarzadegan N, Hawley J, Desai A. Research workforce diversity: The case of balancing national versus international postdocs in research. Syst Res Behav Sci. 2014;31(2 SRCGoogleScholar FG-0):301–15.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1242/prelights.38509

Read preprintSign up to customise the site to your preferences and to receive alerts

Register hereAlso in the scientific communication and education category:

Kosmos: An AI Scientist for Autonomous Discovery

Roberto Amadio et al.

Identifying gaps between scientific and local knowledge in climate change adaptation for northern European agriculture

Anatolii Kozlov

Spurring and Siloing: Identity Navigation in Scientific Writing Among Asian Early-Career Researchers

Jeny Jose

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)