Finding the right words to evaluate research: An empirical appraisal of eLife’s assessment vocabulary

Posted on: 13 May 2024 , updated on: 31 March 2025

Preprint posted on 30 April 2024

Article now published in PLOS Biology at https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3002645

How to clearly and consistently convey the editor and reviewer assessment to readers?

Selected by Benjamin Dominik MaierCategories: scientific communication and education

Updated 31 March 2025 with a postLight by Benjamin Maier

Congratulations to Tom Hardwicke and his team on the publication of their manuscript in PLOS Biology! The journal version is almost identical to the preprint, with only minor formatting adjustments and the addition of a sentence outlining potential future research.

Background

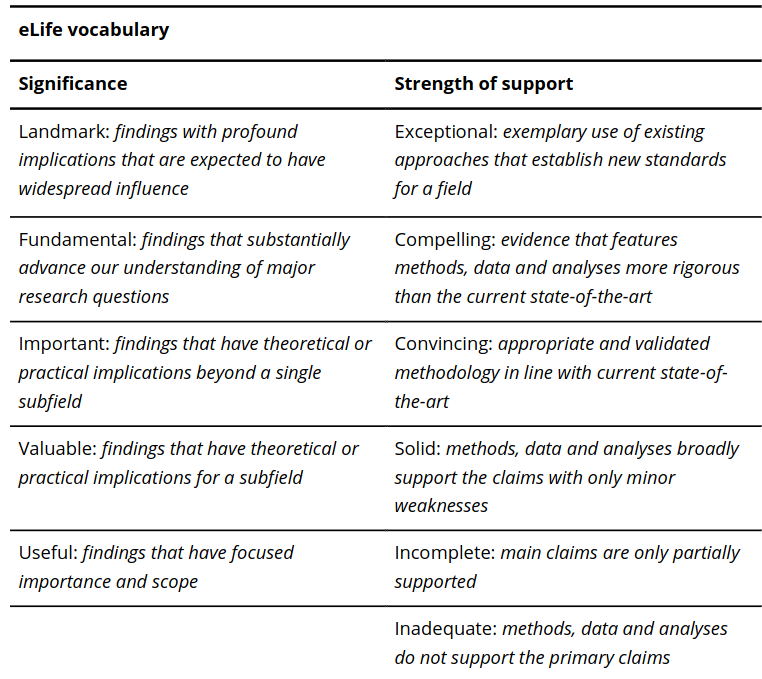

In 2022, the not-for-profit, open access, science publisher eLife announced a new publishing process without the traditional editorial accept/reject decisions after peer review. Instead, all papers that are sent out for peer review are published as “reviewed preprints”. These include expert reviews summarising the findings and highlighting strengths and weaknesses of the study as well as a short consensus evaluation summary from the editor (see eLife announcement). In the eLife assessment, the editor summarises the a) significance of the findings and b) the strength of the evidence reported in the preprint on an ordinal scale (Table 1; check out this link for more information) based on their and the reviewers subjective appraisal of the study. Following peer review, authors can revise their manuscript before declaring a final version. Readers can browse through the different versions of the manuscript, read the reviewer’s comments and the summary assessment.

Table 1. eLife significance of findings and strength of support vocabulary. Table taken from Hardwicke et al. (2024), BioRxiv published under the CC-BY 4.0 International licence.

Study Overview

In this featured preprint, Tom Hardwicke and his colleagues from Melbourne School of Psychological Sciences designed an empirical online questionnaire aimed at evaluating the clarity and consistency of the vocabulary used in the new eLife consensus assessment (as detailed in Table 1). They focussed on determining a) whether diverse readers rank the significance and support strength labels in a consistent order, b) if these rankings correspond with the intended scale, and c) the degree of clarity in distinguishing between the various labels. Additionally, the authors proposed an alternative five-level scale covering the full range of measurement (very strong – strong – moderate – weak – very weak) and compared its perception to eLife’s scale.

The study’s research question, methods, and analysis plan underwent peer review and were pre-registered as a Stage One Registered Report (link). Study participants were sourced globally via an online platform with 301 individuals meeting the inclusion criteria (English proproficiency, aged 18-70 and holding a doctorate degree) and fulfilling attention checks. About one third of the participants indicated that their academic backgrounds aligned closest with disciplines in Life Sciences and Biomedicine. Study participants were presented with 21 brief statements describing the significance and strength of support of hypothetical scientific studies using either the eLife or the alternative proposed vocabulary. They were then tasked to assess the significance and strength of support using 0-100% sliders.

Key Findings

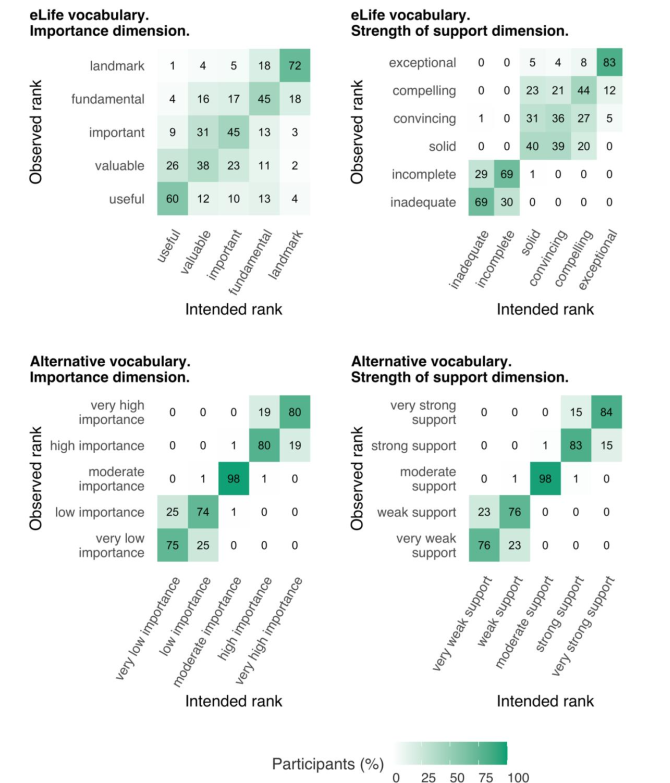

- Only 20% of participants consistently assessed the eLife significance statements in the intended order, while over 60% aligned with the intended rankings using the alternative vocabulary.

- Regarding the strength of support statements, agreements between implied and intended scale were found to be 15% (eLife) and 67% (alternative vocabulary), respectively.

- eLife phrases in the middle of the scale (e.g., “fundamental,” “important,” and “valuable” on the significance dimension) were most frequently misranked by participants (see Figure 1).

- For the alternative scales and the eLife strength of support dimension, participants often misranked the lower and upper ends of the scale by one rank (e.g., very strong vs. strong), attributed by the authors to the difficulty of judging phrases in isolation without knowledge of the underlying scale.

Fig. 1 Comparison between implied and intended rankings of significance and strength of support statements drawn from the eLife and alternative vocabulary. Figure taken from Hardwicke et al. (2024), BioRxiv published under the CC-BY 4.0 International licence.

Conclusion and Perspective

The way scientific knowledge is distributed and discussed is currently experiencing many changes. With the advent of preprint servers, open-access models, transparent review processes, mandates for data and code sharing, creative commons licensing, ORCID recognition, and initiatives like the TARA project under DORA, the aim is to enhance accessibility, inclusivity, transparency, reproducibility, and fairness in scientific publishing. One notable transformation is the introduction of summaries at the top of research articles (e.g. AI-generated summaries on bioRxiv, author summary for PLOS articles and eLife’s assessment summary). Personally, I am quite critical of relying on manuscript summaries and summary evaluations to assess the importance and quality of a research article and decide whether it is worth my time. Instead, I usually skim the abstracts, read the section titles and glance at key figures completely to make a decision.

In this featured preprint, Hardwicke and colleagues evaluate whether the standardised vocabulary used for the eLife assessment statements is clearly and consistently perceived by potential readers. Moreover, they propose an alternative vocabulary which they found to better convey the assessment of the reviewers and editors. Their discussion section features potential approaches to improve the interpretation of these summary statements and outlines different concepts and proposals from other researchers. Overall, the preprint stood out to me as an inspiring example for transparent and reproducible open-science. Tom Hardwicke and colleagues a) pre-registered a peer reviewed report with the research question, study design, and analysis plan (link); b) made all their data, materials and analysis scripts publicly available (link), and c) created a containerised computation environment (link) for easy reproducibility.

doi: Pending

Read preprintHave your say

Sign up to customise the site to your preferences and to receive alerts

Register hereAlso in the scientific communication and education category:

DNA Specimen Preservation using DESS and DNA Extraction in Museum Collections: A Case Study Report

Daniel Fernando Reyes Enríquez, Marcus Oliveira

Kosmos: An AI Scientist for Autonomous Discovery

Roberto Amadio et al.

Identifying gaps between scientific and local knowledge in climate change adaptation for northern European agriculture

Anatolii Kozlov

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)

8 months

Albert Cardona

As far as I know, as an editor at eLife, the controlled vocabulary for the assessment is not aligned along a scale . That a study is of narrow relevance for a subfield or of broad applicability to many fields bears no relationship to importance; it is a mere descriptive summary of the perception of the reviewers and the reviewing editor, all of which are practising scientists, of the potential for applicability of the results. A useful finding may prove transformative, and a landmark finding may prove banal or obvious. To confuse this axis of the eLife assessment for one of importance or “fundability” of future research grants or promotions is to have entirely missed the purpose of the assessment: to transmit to the reader a summary of what the reviewers and editor thought of the findings. No more and no less. If eLife had wanted a “score” for a paper, a numeric scale of 1 through 5 would have been used.