The life of P.I. Transitions to Independence in Academia

Posted on: 3 April 2019 , updated on: 11 April 2019

Preprint posted on 12 March 2019

Article now published in eLife at http://dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.46827

Young PIs in the UK are resilient despite pressure on work-life balance and uncertainty about career perspectives

Selected by Tessa SinnigeCategories: scientific communication and education

Reasons to highlight this preprint

Many of us here at preLights are early career researchers, hoping to make the transition to independent PI positions. But once you get there, what does your life as a starting PI look like? This preprint contains the results of an extensive survey amongst 365 young PIs in the United Kingdom who started their groups within the last 6 years. The preprint is very informative about the current academic landscape and provides recommendations not only for funders and employers, but also for scientists applying for PI positions. We hope that this preprint and future related studies can help empower early career researchers to make the academic career path more productive, more satisfying and more inclusive.

Results of the preprint

The authors of the preprint all recently started their independent positions, and experienced the competitive nature of the road to independence first hand. This inspired them to investigate potential differences in the way that young PIs are recruited, supported and the criteria for promotion across the UK. 365 researchers responded to the survey, the majority of which (~80%) work in life sciences. The preprint contains a detailed analysis of the responses captured in 16 figures, and here I will summarise the characteristics of the cohort and the findings that I found most notable.

The young PIs who responded to the survey had 7 years of postdoc experience on average when starting their position, and the mean age at which they obtained independence was 34 years old. 57% of the respondents were male, which – assuming this is representative for the total pool of young PIs – shows a positive trend towards a better gender balance compared to the current 70% male professors in the UK. 50% of the young PIs were originally from the UK, 30% from the EU, and 20% were from non-EU countries. The researchers had furthermore shown considerable mobility in their careers thus far, many of them having moved between countries for their PhD or postdoc. Finally, nearly all respondents worked full-time, suggesting that leading a research group is not compatible with working part-time. These data sadly confirm the picture of being on temporary postdoc contracts until your mid-30s, which combined with the requirements for international mobility and working full-time is not the most compatible with establishing a stable (family) life.

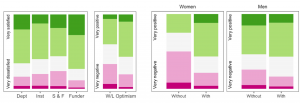

When asked about job satisfaction, the majority of the young PIs were positive about the support from their departments, institutes and funders. However, up to a third was not satisfied with lab space and access to facilities. The biggest challenge appeared to be work-life balance, with 34% dissatisfied. At the same time, a larger fraction was optimistic about their future careers, leading the preprint authors to describe their peers as resilient. However, the discrepancy between the current conditions and hopes for the future can also be interpreted as naivety of the young PIs, which may be taken advantage of. Those who had a mentor were more positive about the future than those without, which made a striking difference especially for women.

Left: figure 4 from the preprint, indicating the satisfaction about support from the department (Dept) and institute (Inst), lab space and access to facilities (S&F), support from the funder, work-life balance (W/L) and optimism for the future. Right: figure 11 from the preprint shows optimism for the future separately for women and men, with and without mentors. Reproduced under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license.

Two major roads can lead to independence in the UK system. About half of the respondents had obtained a lectureship, the other half having been awarded a research fellowship. Whereas lectureships are very teaching-intensive, 57% of the fellows were also expected to teach. The fellows had more postdocs and research assistants in their groups than the lecturers did, because they often have the option to fund these through their fellowships. However, both fellows and lecturers reported difficulties in attracting PhD students. Most PhD studentships in the UK are funded through large doctoral training centres, and the PIs indicated that they struggled both to get their proposals accepted and to find students to join their teams, whereas more senior labs were benefiting from this system. It should also be noted that most young PIs had access to core facilities, yet were required to pay fees to use them. Furthermore, the career perspectives were equally unclear for fellows and lecturers, and the majority of the young PIs were unaware of the criteria for obtaining promotion or a permanent position.

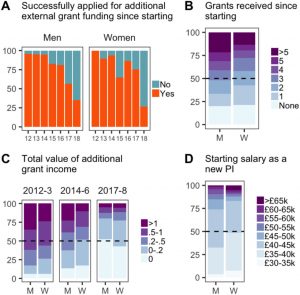

Finally, the survey revealed a pay gap between men and women at several levels: men received higher starting salaries, secured more external funding, and got more start-up funds to establish their labs.

Figure 8 from the preprint showing the differences in funding and starting salary between men and women. Reproduced under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license.

Luckily, the preprint does not just leave us with these concerns, but also provides recommendations for host institutes, funders as well as those about to become PIs themselves. Most notably, host institutes should consider to standardise the starting salaries, and communicate the criteria for career progression more clearly. Funders can similarly recommend a set starting salary for fellowship holders, and ask the host institutes to commit to providing sufficient lab space and access to facilities in the application. Host institutes can address the imbalance in the recruitment of PhD students by prioritising young PIs in the allocation of students, and funders can take action by increasing the availability of individual studentships or by including these in career development fellowships or awards. New PIs, finally, should be more critical when interviewing and negotiating once they are offered a position. Discuss the details such as who will provide basic lab equipment, insist on getting the starting salary that is recommended for the position, ask about the promotion criteria and talk to other PIs in the department.

Questions & future directions

How does the UK system compare to that in other countries? Would you say that the fellowship route benefits early career researchers? Are there any data how many of the fellows obtain a permanent position, and/or are you planning to follow up on this cohort?

It would be interesting to know more about the mentoring schemes for young PIs. For example, are they assigned a mentor or can they choose one? Are the schemes typically run within a department or more widely across the institute? From the survey it seems that mentoring can really make a big difference, so it would be good to know which schemes are most successful.

The underlying problem that drives competition and a poor work-life-balance, especially in life sciences, appears to be the shortage of funding, compared to the number of people who want to stay in research. What can be done at this level? Should we create more positions for staff scientists, rather than forcing everyone down the PI route, and how could these positions be funded? Should we make more effort to train students for alternative careers, or even restrict the numbers of PhD students?

Related blog posts

MRC insight blog, Transitioning to research independence, 21 March 2019

doi: https://doi.org/10.1242/prelights.9826

Read preprintSign up to customise the site to your preferences and to receive alerts

Register hereAlso in the scientific communication and education category:

DNA Specimen Preservation using DESS and DNA Extraction in Museum Collections: A Case Study Report

Daniel Fernando Reyes Enríquez, Marcus Oliveira

Kosmos: An AI Scientist for Autonomous Discovery

Roberto Amadio et al.

Identifying gaps between scientific and local knowledge in climate change adaptation for northern European agriculture

Anatolii Kozlov

(1 votes)

(1 votes)