Identifying gaps between scientific and local knowledge in climate change adaptation for northern European agriculture

Posted on: 30 July 2025 , updated on: 31 July 2025

Preprint posted on 25 June 2025

Agricultural knowledge gaps, or pluralism, depicting, and participation as a route to climate adaptation.

Selected by Anatolii KozlovCategories: ecology, scientific communication and education

When I saw the title of this preprint, it got me really excited, because it touches upon one of my favourite problems, that of the tensions between theory and practice, knowing-why and knowing-how, knowing from testimony or knowing first-hand.

Now, these categories are, probably, more familiar to some than to others, so it’s worth pointing out, for instance, that as social beings, we are never confined only to our own devices; lots of things we know (or assume to know) are thanks to our family, friends, colleagues, wider community and culture. Science is a wonderful example of that. The experiment one does in the lab today, materially and conceptually, most often relies on experiments done elsewhere in the world. This flow of knowledge is always a conjunction of one’s first-person knowledge (often practical) with someone else’s testimony, which, in its turn, is also a mix of first-person knowledge with someone else’s testimony, and so on and so forth. On the one hand, this points to an image of knowledge as a complex, entangled and constantly rewoven web; or a fabric; or a patchwork (made from patches of specialised knowledge). On the other hand, there can be gaps and tensions between different specialised knowledge-perspectives.

The agricultural science perspective and farmer’s perspective on climate adaptation are at the focus of this preprint. The authors make it clear why this is a question of the utmost significance. At the end of the day, farmers are the key players in food production. They are the ones who know the process of growing crops the most intimately. They are also the ones who are practically coping with the changing environmental conditions of food growth. So, if we are to devise and implement efficient adaptive strategies, sensitive to the challenges on the ground as well as involving climate-smart farming solutions, it is imperative that we co-develop shared knowledge of the multifaceted climate challenge. Mapping knowledge gaps is a step in that direction.

How does one capture those? That is a tricky part. Academic researchers organise their knowledge exchange around shared tools and conventions, such as peer-reviewed articles (and preprints!), which can be analysed in bulk. For farmers, musicians, chess-players, plumbers and practitioners of most other trades, writing peer-reviewed research articles is not part of the professional routine. One needs some kind of content, data that can be compared meaningfully between the two parties. And, well, in a nutshell, the solution was to literally make scientists and farmers depict a map of factors relevant to the problem at hand. This form of diagramming has a fancy name, Influence Diagram, draws its academic lineage from the concepts of mental models and probabilistic analysis, but beyond that, I think the magic of it lies in that diagramming is a low-threshold tool for setting up a conceptual dialogue between different professional communities.

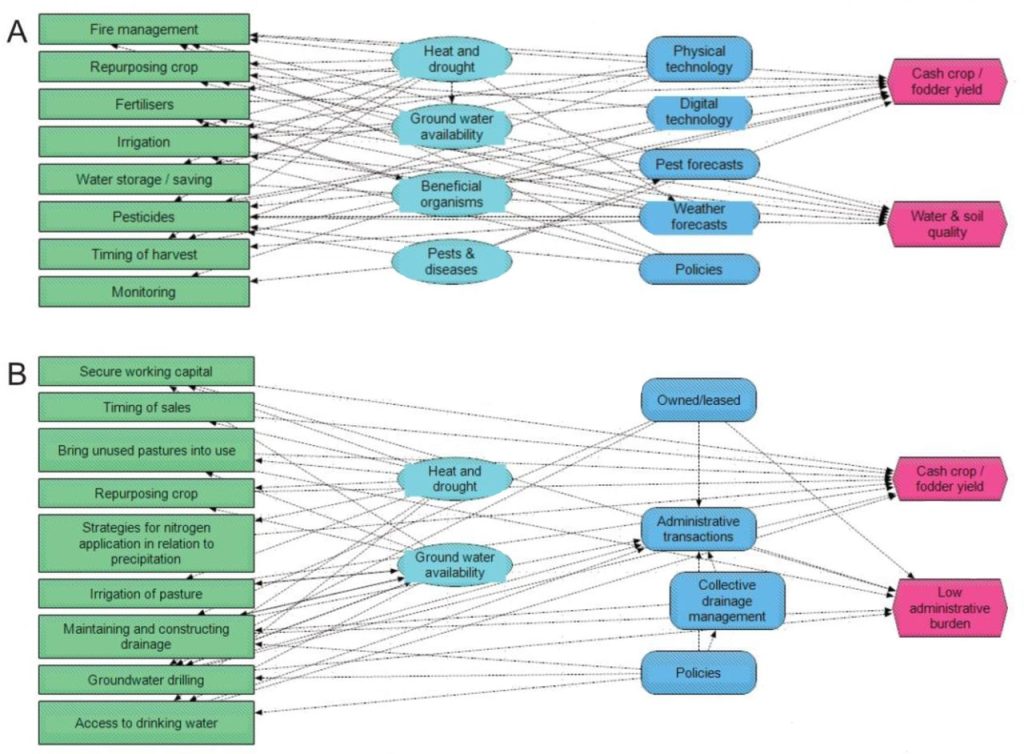

The researchers behind this work (all of them are from Sweden) invited local farmers for a participative semi-structured workshop. The aim of the workshop was to produce diagrams that would faithfully represent farmers’ understanding of crisis-management and adaptive strategies related to the event of the 2018 heatwave and the drought in Scania, a region of Sweden. Prior to that, the researchers produced similar diagrams of their own that drew on the insights from a scoping review of scientific literature on the same event (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Influence diagrams depicting crisis management in crop production during the 2018 combined heat and drought event as seen by scientists (A) and farmers (B). The nodes represent decisions (green rectangles), chance variables that can be influenced by the decision-maker (light blue ovals), variables that cannot be directly influenced by the decision-maker (dark blue rounded rectangles), and objectives (red hexagons). CC BY 4.0 license.

Comparing the two diagrams, some curious differences surfaced. For example, scientists tended to focus on generalisable technology-oriented solutions, while the farmers’ suggestions and actions were more concrete and grounded in the socio-economic and administrative specificities of their farms. Moreover, farmers identified things beyond their individual farms (for example, collective drain-management) as important variables for successful adaptation. This potentially indicated their understanding of adaptive decision-making as collective and multi-actor practice, rather than (just) a technological problem. This is an interesting observation, since, as the authors note, “historically, agricultural knowledge transfer followed a top-down model, i.e. considering knowledge from authorities and scientists, while marginalising farmers’ insights” . The danger of this, as the study illustrates, is it may lead to favouring technological solutions, while ignoring the social and practical dimensions of the problem.

Overall, these observations aren’t meant to decide who is right or wrong. Rather, they invite one to explore the ways forward that would combine the two perspectives. Indeed, as the authors suggest, their exploratory study is meant to help formulate further context-sensitive questions, which can be tested through quantitative surveys. Such an enquiry would provide an empirical basis for more adequate policy-making and communication.

And this marks another reason why I really liked this work. To my mind, the study illustrates that in the face of multifaceted challenges, we need to practice genuinely interdisciplinary and creative thinking, in which natural sciences, social sciences and humanities complement each other.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1242/prelights.41122

Read preprintSign up to customise the site to your preferences and to receive alerts

Register hereAlso in the ecology category:

Cannibalism as a mechanism to offset reproductive costs in three-spined sticklebacks

Tina Nguyen

Trade-offs between surviving and thriving: A careful balance of physiological limitations and reproductive effort under thermal stress

Tshepiso Majelantle

The cold tolerance of an adult winter-active stonefly: How Allocapnia pygmaea (Plecoptera: Capniidae) avoids freezing in Nova Scotian winters

Stefan Friedrich Wirth

Also in the scientific communication and education category:

Kosmos: An AI Scientist for Autonomous Discovery

Roberto Amadio et al.

Identifying gaps between scientific and local knowledge in climate change adaptation for northern European agriculture

Anatolii Kozlov

Spurring and Siloing: Identity Navigation in Scientific Writing Among Asian Early-Career Researchers

Jeny Jose

preLists in the ecology category:

SciELO preprints – From 2025 onwards

SciELO has become a cornerstone of open, multilingual scholarly communication across Latin America. Its preprint server, SciELO preprints, is expanding the global reach of preprinted research from the region (for more information, see our interview with Carolina Tanigushi). This preList brings together biological, English language SciELO preprints to help readers discover emerging work from the Global South. By highlighting these preprints in one place, we aim to support visibility, encourage early feedback, and showcase the vibrant research communities contributing to SciELO’s open science ecosystem.

| List by | Carolina Tanigushi |

November in preprints – DevBio & Stem cell biology

preLighters with expertise across developmental and stem cell biology have nominated a few developmental and stem cell biology (and related) preprints posted in November they’re excited about and explain in a single paragraph why. Concise preprint highlights, prepared by the preLighter community – a quick way to spot upcoming trends, new methods and fresh ideas.

| List by | Aline Grata et al. |

Biologists @ 100 conference preList

This preList aims to capture all preprints being discussed at the Biologists @100 conference in Liverpool, UK, either as part of the poster sessions or the (flash/short/full-length) talks.

| List by | Reinier Prosee, Jonathan Townson |

preLights peer support – preprints of interest

This is a preprint repository to organise the preprints and preLights covered through the 'preLights peer support' initiative.

| List by | preLights peer support |

EMBO | EMBL Symposium: The organism and its environment

This preList contains preprints discussed during the 'EMBO | EMBL Symposium: The organism and its environment', organised at EMBL Heidelberg, Germany (May 2023).

| List by | Girish Kale |

Bats

A list of preprints dealing with the ecology, evolution and behavior of bats

| List by | Baheerathan Murugavel |

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)