Bundling and segregation affects “liking”, but not “wanting”, in an insect

Posted on: 16 June 2022

Preprint posted on 26 May 2022

Article now published in eLife at http://dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.79314

The best things come in small packages: ants value segregated rewards over bundled rewards

Selected by Lucy NevardCategories: animal behavior and cognition, ecology

Context

Humans regularly make irrational decisions, often shaped by their flawed perception of an object’s value. Value perception can be influenced by many factors, such as the surrounding context or individual expectations prior to encountering a set of options. Errors in value perception are widely exploited in marketing strategies. This phenomenon is also seen in non-human animals, including insects, which are increasingly found not to be merely rational agents. Bees, for example, assess value contingent on the context, the presence of other options (the “decoy effect”), and previous experiences, potentially allowing flowers to take advantage of these cognitive quirks in a similar way to marketing strategists.

One phenomenon known to behavioural economists is the bundling versus segregation effect: options bundled together (integrated) are perceived as less valuable (and conversely, less costly) than those presented separately. For this reason, people tend to prefer bundled losses and segregated gains. Consumers often spend more overall (higher costs) when products are presented as a bundle than when they are sold separately, for example when paying for a hotel room which “includes” breakfast. This effect is well-established in humans, but surprisingly has not yet been studied in animals.

The authors of this preprint investigated the bundling versus segregation effect using ants (Lasius niger) as their model system. One benefit of researching ants is their eusociality, which adds another layer of complexity and significance to the study. After consuming a food reward, ants can recruit their nestmates by depositing pheromones, allowing researchers to distinguish between two measures of reward value: “wanting” and “liking”. If an ant chooses an option, this is “wanting” – if it then deposits pheromones, this is “liking”, and indicates that the reward is perceived as good-quality. The distinction between “wanting” and “liking” has been established in humans and rats but has not been explored in insects before.

Set-up and research questions

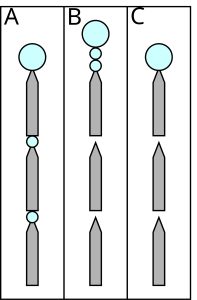

The authors designed distinct “runways” in which rewards and costs were spatially arranged in different ways but with equal overall values (Figure 1). Rewards were drops of sugar solution and costs were the distances travelled (ants prefer walking shorter distances to rewards, as I’m sure we can all relate to!). Individual ants were trained to associate different odours with distinct runways, and then allowed to choose between these odours in a Y-maze (a pairwise choice). The overarching question of this study is: does the segregation of rewards or costs affect either “wanting” (choice) or “liking” (pheromone deposition)?

Key findings

- In a pilot experiment, the authors establish that ants perceive longer distances as more costly, preferring to walk shorter distances to rewards. Such a preference has previously been assumed, but this study provides the first empirical evidence for it, and allows the researchers to use segment distance as a “cost” in their main experiments.

- Segregation of rewards does not affect “wanting”. Ants did not consistently choose one of the scenarios over another when given binary choices. In other words, bundling or segregation of costs or rewards does not affect how much they “want” an option.

- Bundling does affect “liking”. Overall, ants deposited the most pheromone when costs were bundled and rewards segregated (lowest cost and highest reward) (scenario B in Figure 2). This indicates that bundling and segregation affect value perception in ants in a manner similar to humans.

Why I chose this preprint

The title was instantly intriguing to me! This study offers some fantastic new findings: it is the first demonstration in insects that the bundling and segregation of rewards can affect value perception. I am particularly interested in the novel distinction between “liking” and “wanting”, which hasn’t been studied in insects before, despite their recruitment methods and collective foraging. The findings of this preprint add to our understanding of insect decision-making and provide a model for further studies on value perception and the distinction between “liking” and “wanting” in social insects.

Questions to the authors

- Do you think runway segments of different lengths, as well as imposing differing costs, also affect an ant’s motivation to drink to satiation? For example, after walking for 75cm without a reward, they may be more motivated than if they’d had rewards along the way?

- Is there substantial variation between individuals in “liking” or “wanting”? For example, are some individuals more likely to deposit pheromones regardless of experimental treatment?

- Would you expect to find a similar “bundling vs segregation” effect in non-social invertebrates (assuming you could assess their perception of reward value)? Or do you think a preference (in “liking”) for segregated rewards is particular to social animals? For example, could it benefit social insects to recruit nestmates to multiple small rewards which are likely to be more reliable and perhaps more efficient to collect than one large source?

- Do you have any expectations about ant preferences (either “liking” or “wanting”) if they were simultaneously given all three options to choose from?

Further reading

Berridge KC. 2018. Evolving Concepts of Emotion and Motivation. Frontiers in Psychology 9.

Czaczkes TJ, Brandstetter B, di Stefano I, Heinze J. 2018a. Greater effort increases perceived value in an invertebrate. J Comp Psychol 132:200–209.

De Agrò M, Grimwade D, Bach R, Czaczkes TJ. 2021. Irrational risk aversion in an ant. Anim Cogn.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1242/prelights.32309

Read preprintSign up to customise the site to your preferences and to receive alerts

Register hereAlso in the animal behavior and cognition category:

Cannibalism as a mechanism to offset reproductive costs in three-spined sticklebacks

Tina Nguyen

Morphological variations in external genitalia do not explain the interspecific reproductive isolation in Nasonia species complex (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae)

Stefan Friedrich Wirth

Trade-offs between surviving and thriving: A careful balance of physiological limitations and reproductive effort under thermal stress

Tshepiso Majelantle

Also in the ecology category:

Resilience to cardiac aging in Greenland shark Somniosus microcephalus

Theodora Stougiannou

Cannibalism as a mechanism to offset reproductive costs in three-spined sticklebacks

Tina Nguyen

The cold tolerance of an adult winter-active stonefly: How Allocapnia pygmaea (Plecoptera: Capniidae) avoids freezing in Nova Scotian winters

Stefan Friedrich Wirth

preLists in the animal behavior and cognition category:

Biologists @ 100 conference preList

This preList aims to capture all preprints being discussed at the Biologists @100 conference in Liverpool, UK, either as part of the poster sessions or the (flash/short/full-length) talks.

| List by | Reinier Prosee, Jonathan Townson |

9th International Symposium on the Biology of Vertebrate Sex Determination

This preList contains preprints discussed during the 9th International Symposium on the Biology of Vertebrate Sex Determination. This conference was held in Kona, Hawaii from April 17th to 21st 2023.

| List by | Martin Estermann |

Bats

A list of preprints dealing with the ecology, evolution and behavior of bats

| List by | Baheerathan Murugavel |

FENS 2020

A collection of preprints presented during the virtual meeting of the Federation of European Neuroscience Societies (FENS) in 2020

| List by | Ana Dorrego-Rivas |

Also in the ecology category:

SciELO preprints – From 2025 onwards

SciELO has become a cornerstone of open, multilingual scholarly communication across Latin America. Its preprint server, SciELO preprints, is expanding the global reach of preprinted research from the region (for more information, see our interview with Carolina Tanigushi). This preList brings together biological, English language SciELO preprints to help readers discover emerging work from the Global South. By highlighting these preprints in one place, we aim to support visibility, encourage early feedback, and showcase the vibrant research communities contributing to SciELO’s open science ecosystem.

| List by | Carolina Tanigushi |

November in preprints – DevBio & Stem cell biology

preLighters with expertise across developmental and stem cell biology have nominated a few developmental and stem cell biology (and related) preprints posted in November they’re excited about and explain in a single paragraph why. Concise preprint highlights, prepared by the preLighter community – a quick way to spot upcoming trends, new methods and fresh ideas.

| List by | Aline Grata et al. |

Biologists @ 100 conference preList

This preList aims to capture all preprints being discussed at the Biologists @100 conference in Liverpool, UK, either as part of the poster sessions or the (flash/short/full-length) talks.

| List by | Reinier Prosee, Jonathan Townson |

preLights peer support – preprints of interest

This is a preprint repository to organise the preprints and preLights covered through the 'preLights peer support' initiative.

| List by | preLights peer support |

EMBO | EMBL Symposium: The organism and its environment

This preList contains preprints discussed during the 'EMBO | EMBL Symposium: The organism and its environment', organised at EMBL Heidelberg, Germany (May 2023).

| List by | Girish Kale |

Bats

A list of preprints dealing with the ecology, evolution and behavior of bats

| List by | Baheerathan Murugavel |

(1 votes)

(1 votes)