Evaluating features of scientific conferences: A call for improvements

Posted on: 28 April 2020

Preprint posted on 21 April 2020

Article now published in Nature Human Behaviour at http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01067-y

Categories: scientific communication and education

The scientific conference – as we know it – is finished.

The death knell for the modern scientific conference had already been sounded some time before the coronavirus pandemic began to sweep the globe a little over 100 days ago. Even the most ardent advocates of scientific meetings agree that existing models for bringing researchers together to share and discuss their work are simply not sustainable, in the midst of climate change, aggressive border policing and mushrooming global inequality.

I write this as one of those ardent advocates, a self-confessed conference junkie. I love (almost) everything about the meetings I’ve attended over the years – sharing and absorbing new science, rediscovering favourite places and old haunts, reuniting with old friends, connecting with new ones, building collaborations or maybe just arguing politics over a cup of coffee or a beer. Each time, I return home refreshed, reenergised, full of new plans and ideas. I stride to the lab the next morning with a spring in my step, raring to go.

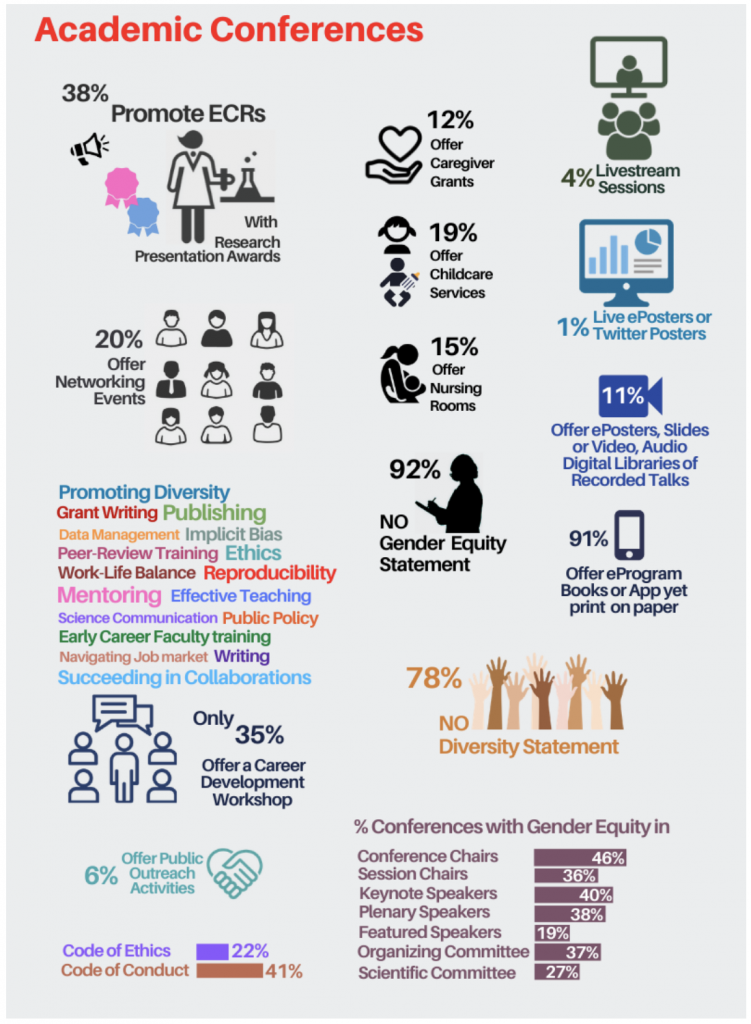

Yet, these small joys reflect an unhealthy dose of privilege and obscure a massive hidden cost – issues illustrated with painful clarity by Sarabipour et al. in their recent, thorough analysis of over 260 scientific conferences held between 2018 and 2020. The air travel of a single attendee of just one international conference can generate a carbon footprint that dwarfs the per capita CO2 output of many countries. Moreover, conferences can be prohibitively expensive and, on average, tend to amplify pre-existing societal inequalities (some examples in Figure 1) – issues characterised in quantitative detail by the authors. Despite a growing clamour for change from the scientific community and massive advances in digital networking technology, the format of the average meeting has changed little over the preceding decades. However, hundreds of conferences have been cancelled or postponed courtesy the COVID19 pandemic, providing us with an unexpected and unprecedented opportunity to enact a paradigm shift – if we act quickly and decisively.

The tour-de-force by Sarabipour et al. is the first step in the right direction: let’s use this lockdown period to bid our goodbyes to a conference format that has outlived its usefulness, but make sure to replace it with something better.

How do we fix this?

The authors propose a comprehensive program of conference reform: replacing most conferences with virtual or semi-virtual (in which attendees congregate in-person at local hubs to participate in a virtual programme) meetings that take full advantage of immersive and interactive video conferencing tools; supporting ground-based travel to small regional meetings; a stronger drive for intersectional equality and enhanced early career researcher (ECR) support; and integrating conferences with open research dissemination and peer review through the preprint ecosystem.

To my knowledge, the work by Sarabipour et al. represents the most detailed and well-structured conference reform programme in the literature to date: scientific conference organisers around the world should engage with and help hone their proposal further. Now is the time: with meetings, seminar series, workshops, and journal clubs rapidly pivoting to online formats under pandemic-induced lockdowns, we have a golden opportunity to sort through innovations that work and those that require further tweaking.

I spoke to the authors of the preprint, as well as a few colleagues, to collate their perspectives; here are a few comments of my own.

Use the COVID19 pandemic as a massive, transparent data-gathering exercise

The urgent need for reform long predates the current pandemic, and many successful examples of virtual and semi-virtual conferences already exist (e.g. here, here and here [1-3]). However, the trickle has become a flood – many scientists around the world will attend or have attended their first ever virtual conference this summer, myself included. In addition to participant demographics and overall attendance, virtual conference organisers have access to data that would be tricky or impossible to track normally – audience engagement and participation, for example. In combination with participant surveys, this data should be collected – and, ideally, widely shared for others to analyse and learn from.

Make the asynchronous nature of online communication a feature rather than a bug

As the authors are also at pains to point out, just porting all the features – and bugs – of in-person conferences online is unnecessary and will simply not work. To pick just one example from the preprint, virtual conferences need not be tied to a packed 3-day or 5-day schedule – and the data-sharing and discussion facets of meetings can be clearly separated. Talks can and should be recorded to allow participants from all time zones, or with conflicting commitments, to access them, while actual discussions can be linked to other communication tools (Slack, preprint discussion sites). More importantly, discussions with a speaker could be given a chance to gain momentum – beginning before the seminar and continuing after.

Create permanent local hubs through in-house video conferencing facilities

Wherever possible, university departments and research institutes should be funded (perhaps through a repurposing of a portion of travel funding?) to refit one of their seminar or large meeting rooms for state-of-the-art remote conferencing – with a flexible layout designed to accommodate both workshop and seminar formats. This will create a “hub” to power the authors’ “semi-virtual” conference format, but could also support, for example, one-off virtual seminars, grant consortium meetings and review panel discussions. In the near future, one could envision these facilities incorporating virtual reality capabilities or other technologies that would be difficult or expensive for individuals to install at home or in offices.

The internet should be a basic human right

The deep-rooted societal inequalities that poison conferences will in all likelihood simply be transferred in toto to the digital domain as long as internet access is a commodity for sale subject to government control. We are already seeing evidence of this during the early stages of the COVID19 pandemic and in crackdowns by autocratic societies around the world. As more and more of our professional life is transferred online, I believe that scientists must join the call for internet access to be declared a fundamental human right [4, see also here and here].

When we do meet in person, it has to be worth the cost

For those of us who have been fortunate enough to attend well-organised meetings, the serendipitous connections made over coffee, during a chance encounter in the corridor, or at the social events at the end of each day are the standout feature. In my own relatively short career thus far, these connections have evolved into collaborations, job opportunities, and lasting friendships. However, overall, these events are rare – for each new friend made, I can recount several stories of terrible sessions running overtime with speakers droning on about work published years ago, that I flew thousands of kilometres to listen to. We must acknowledge that it is a huge privilege, shared by only a tiny fraction of all the scientists in the world, to be able to access the physical spaces provided by meetings frequently enough to make them really count. Significant intellectual and financial resources should be channeled into making a sustainable number of in-person meetings embody that spirit of human connection, while ensuring that not only the privileged attend. Small workshops and regional meetings can meet these criteria: local, allowing the majority of attendees to use ground-based transport; democratic, with everyone, from the tenured professor to the senior graduate student given the same speaking opportunities; immersive, drawing people together and away from the demands of their daily work lives. The much-loved UK-based workshops organised by the Company of Biologists tick some of these boxes, and could serve as a starting template for many organisers going forward.

In summary

I could go on, but let me summarise here for now. The tour-de-force by Sarabipour et al. is the first step in the right direction: let’s use this lockdown period to bid our goodbyes to a conference format that has outlived its usefulness, but make sure to replace it with something better.

References

- Abbott, A. Low-carbon, virtual science conference tries to recreate social buzz. Nature 577, 13 (2020).

- Gichora, N. N. et al. Ten Simple Rules for Organizing a Virtual Conference—Anywhere. PLoS Comput. Biol. 6, e1000650 (2010).

- Achakulvisut, T. et al. Improving on legacy conferences by moving online. Elife 9, (2020).

- Reglitz, M. The Human Right to Free Internet Access. J. Appl. Philos. (2019). doi:10.1111/japp.12395

Acknowledgements

I’d like to thank the authors for committing time to engage and chat; everyone who commented on this post; all the colleagues who gave me feedback, including Jan Skotheim, Buzz Baum, Lucy Collinson, Frank Norman, Jennifer Rohn, and Andre Brown; and Mate Palfy for going over and above on supporting this post.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1242/prelights.19630

Read preprintGary McDowell

Great piece! I’m a co-author on a recent article about making conference and meeting events more inclusive, from the perspective of a group who work on making biology education spaces more inclusive and equitable. I’m sharing the article here in case its of interest! This time is certainly an opportunity to reimagine the nature and structure of conferences and similar events.

Article: Insights from the iEMBER Network: Our Experience Organizing Inclusive Biology Education Research Events (https://www.asmscience.org/docserver/fulltext/jmbe/21/1/jmbe-21-34.pdf?expires=1589240122&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=D3DB2E7A168B0E4BB5E9A42D1C1B9E18)

Have your say

Sign up to customise the site to your preferences and to receive alerts

Register hereAlso in the scientific communication and education category:

DNA Specimen Preservation using DESS and DNA Extraction in Museum Collections: A Case Study Report

Daniel Fernando Reyes Enríquez, Marcus Oliveira

Kosmos: An AI Scientist for Autonomous Discovery

Roberto Amadio et al.

Identifying gaps between scientific and local knowledge in climate change adaptation for northern European agriculture

Anatolii Kozlov

(2 votes)

(2 votes)

6 years

Ram

Great post! Much needed for the ‘new normal’. It’s good to see the facts and stats although most of us knew the downsides of conferences and meetings. I was an MSCA fellow and I was ‘spoiled’ with the lavish funding. I guess as scientists we should be much more critical about our way of life and research, not to mention the dier times we are facing now.