Tapping into non-English-language science for the conservation of global biodiversity

Posted on: 18 June 2021

Preprint posted on 26 May 2021

Article now published in PLOS Biology at http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001296

“English only please!” Real world effects of English-centred literature searches.

Selected by Paul Gerald L. Sanchez and Stefano VianelloCategories: ecology, scientific communication and education

Background

“Whose knowledge, voices, stories, and experiences are being represented; whose knowledge do we consider valid and important, whose knowledge are we learning from?” Knowledge Equity Lab (https://knowledgeequitylab.ca/)

The hegemony of the English language within academia is self-evident, with figures reporting more than 90% of scientific publications being written in English. The (apparent) unquestionability of such status quo is so entrenched in the collective that most people would not bat an eye when coming across bibliographies made up, in their entirety, of references written in English. And this may indeed not only be the norm, but the expectation when we* perform literature searches, when we write our own papers and theses, when we review the appropriateness of a colleague’s references in a submitted manuscript. The bibliography of that paper we are preparing right now? Only English-written references. And because we look for (and see all around us) knowledge written in English, we might start to believe that knowledge is written in English, it just is.

(*this highlight is written with the expectation of a majoritary (white) Western Academic readership. As such, what is here defined as “our”, “we”, “us”, “normal” is to be interpreted accordingly)

Yet, knowledge producers exist and produce knowledge all around the globe. And in its simplicity and self-evidence this acknowledgment is revolutionary. Not only because it de-centres knowledge production away from it being an exclusive export of English-writing Western Academic spaces, but also because it means that knowledge is accordingly produced in a varied range of languages. As predominant as English-written scientific literature may be, literature searches that only source from it (and the conclusions coming from such searches!) are thus incomplete. But does that really necessarily introduce gaps? Biases?

We may all, to different degrees, hold preconceived (or instilled) notions about non-English scientific knowledge, and use them as a justification of English-centred literature searches:

- “The amount of literature I am missing when only searching English texts is negligible anyway”

- “Even if I were to be missing relevant literature, such missing amount is ever decreasing as people shift to English”

- “I am anyways only missing “lower quality” research”

- “Someone else, somewhere, will have published the same results in English, so I am not really missing anything”

Here comes the preprint I would like to highlight here. In this preprint, a multi-lingual team of authors screened over 419000 (!) peer-reviewed papers, across 16 languages, to systematically address each of the preconceptions listed above, and test whether these are grounded on evidence, or whether they are simply misconceptions.

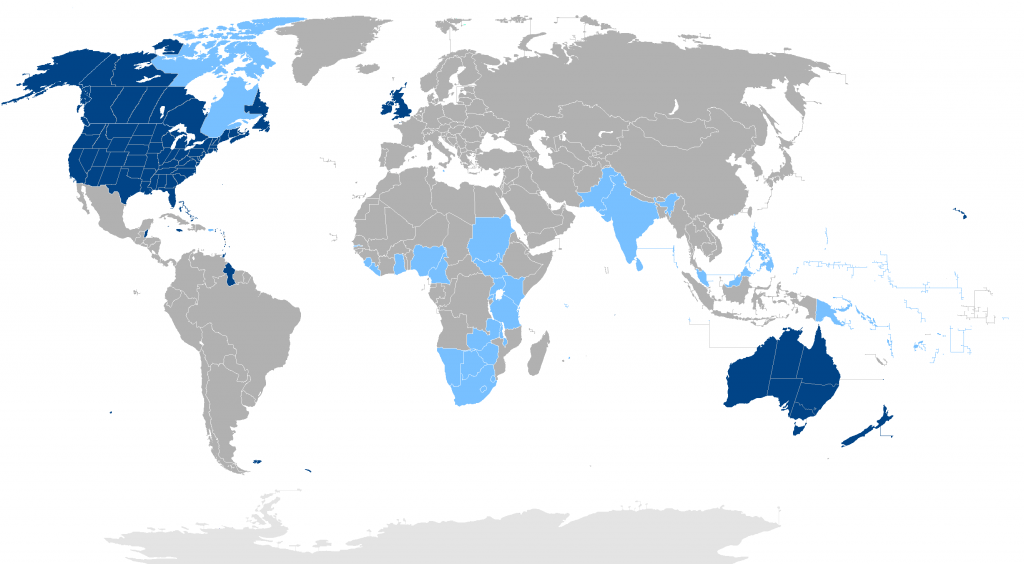

The paper is one of few of its kind where the actual impact of including/excluding non-English literature is translated in quantitative terms and real world examples. In the specific case of this preprint, the field is global biodiversity conservation research. Indeed the preprint opens with a damning statement: that if one looks at evidence synthesis approaches in the field to date (which in turn inform biodiversity conservation policies!), these have ignored non-English science. While this would be damning regardless, it is even more so given that areas of rich biodiversity concentrate in countries that speak languages other than English.

FIGURE 1: Countries in the world where English is the native language (dark blue), where it is an official language (but not majority language; light blue), and where it is neither (grey). CC-BY https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Anglospeak.png

Main results

By screening 419,680 peer-reviewed papers across 16 languages, the authors show that most of the preconceived notions listed above – at least in the field they analysed (global conservation research)- are indeed misconceptions:

- “The amount of literature I am missing when only searching English texts is negligible anyway”

False. One third of all relevant papers to the topic were written in languages other than English. In other words, an evidence synthesis search restricted to English-written texts would only find two thirds of all relevant information.

- “Even if I were to be missing relevant literature, such missing amount is ever decreasing as people shift to English”

False. The number of relevant studies written in languages other than English has been increasing every year (especially for languages like Portuguese, Russian, and traditional Chinese)

- “Someone else, somewhere, will have published the same things in English, so I am not really missing anything” (i.e. English literature is a random sample of all literature)

False. Articles written in languages other than English expand the geographical range of documented biodiversity conservation interventions by 25%. Many non-English studies are actually providing data on areas that are not covered by any English counterpart. In the specific case of this preprint, an English-centred search would have lost 5%, 32%, and 9% of the evidence on amphibian, bird, and mammal species, respectively. Regarding articles on the conservation of threatened species, it would have lost 23% of the coverage on bird species.

The authors however do find a correlation between research written in languages other than English, and, on average, less robust study designs.

Overall, the authors show that – at least for the field of biodiversity conservation – the focus on English-literature translates in a loss of ⅓ of relevant literature, and of unique literature as such. Accordingly, evidence synthesis that does not include non-English literature ends up with avoidable gaps, and these gaps often concern areas/communities most affected by issues of biodiversity conservation and that would therefore be most affected by global initiatives on conservation. Finally, ignoring non-English publications also often means ignoring knowledge produced by local practitioners, that is those very knowledge producers with the closest ties to the topics they are investigating.

Questions for the authors

- In the paper, you find, on average, a lower level of robustness for evidence presented in non-English texts. Yet it is difficult to imagine a causative link between the robustness of reported data, and the language in which such data would be communicated (i.e. the “form” this data takes when shared). How do you explain the observation?

- Your report (and the authors list!) underscores the point that complete, relevant synthesis requires multilingual teams of researchers. Could you comment on this? Are there platforms/initiatives that would facilitate access to non-English science by monolingual (teams of) researchers?

- As a mirror to the point above, and much more importantly, are there initiatives in place to facilitate the access to English-literature by non-English-speaking knowledge-producers (a much more pressing problem given the disparities created by English language hegemony)?

- Did the authors find it more difficult to access and find non-English literature? What role do western publishing models play in establishing/reinforcing the biases described in the text?

- The authors focus on a topic (biodiversity conservation) relevant to countries where English is not the first language, yet whose evidence synthesis strategies ignore non-English literature. Is this highlighting an English-speaking academic world ignoring the voices from the very communities that should be leading efforts on the topic?

- The preprint encourages to “tap into” and “uncover” non-English science. Could you clarify the intended readership of this work? Are non-English speaking communities also under-acknowledging literature that is not written in English? Would invites to “tap into” and “uncover” better be framed as calls to acknowledge/stop ignoring scholarship written in other languages?

#—————————————–

Further reading:

Gordin, Michael D. “Introduction: Hegemonic languages and science.” Isis 108.3 (2017): 606-611.

Ramírez-Castañeda, Valeria. “Disadvantages in preparing and publishing scientific papers caused by the dominance of the English language in science: The case of Colombian researchers in biological sciences.” PloS one 15.9 (2020): e0238372.

Gordin, Michael D. Scientific Babel: How science was done before and after global English. University of Chicago Press, 2015.

Angulo, Elena, et al. “Non-English languages enrich scientific knowledge: The example of economic costs of biological invasions.” Science of the Total Environment 775 (2021): 144441.

Nuñez, Martin A., and Tatsuya Amano. “Monolingual searches can limit and bias results in global literature reviews.” Nature Ecology & Evolution 5.3 (2021): 264-264.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1242/prelights.29514

Read preprintHave your say

Sign up to customise the site to your preferences and to receive alerts

Register hereAlso in the ecology category:

Resilience to cardiac aging in Greenland shark Somniosus microcephalus

Theodora Stougiannou

Cannibalism as a mechanism to offset reproductive costs in three-spined sticklebacks

Tina Nguyen

Trade-offs between surviving and thriving: A careful balance of physiological limitations and reproductive effort under thermal stress

Tshepiso Majelantle

Also in the scientific communication and education category:

DNA Specimen Preservation using DESS and DNA Extraction in Museum Collections: A Case Study Report

Daniel Fernando Reyes Enríquez, Marcus Oliveira

Kosmos: An AI Scientist for Autonomous Discovery

Roberto Amadio et al.

Identifying gaps between scientific and local knowledge in climate change adaptation for northern European agriculture

Anatolii Kozlov

preLists in the ecology category:

SciELO preprints – From 2025 onwards

SciELO has become a cornerstone of open, multilingual scholarly communication across Latin America. Its preprint server, SciELO preprints, is expanding the global reach of preprinted research from the region (for more information, see our interview with Carolina Tanigushi). This preList brings together biological, English language SciELO preprints to help readers discover emerging work from the Global South. By highlighting these preprints in one place, we aim to support visibility, encourage early feedback, and showcase the vibrant research communities contributing to SciELO’s open science ecosystem.

| List by | Carolina Tanigushi |

November in preprints – DevBio & Stem cell biology

preLighters with expertise across developmental and stem cell biology have nominated a few developmental and stem cell biology (and related) preprints posted in November they’re excited about and explain in a single paragraph why. Concise preprint highlights, prepared by the preLighter community – a quick way to spot upcoming trends, new methods and fresh ideas.

| List by | Aline Grata et al. |

Biologists @ 100 conference preList

This preList aims to capture all preprints being discussed at the Biologists @100 conference in Liverpool, UK, either as part of the poster sessions or the (flash/short/full-length) talks.

| List by | Reinier Prosee, Jonathan Townson |

preLights peer support – preprints of interest

This is a preprint repository to organise the preprints and preLights covered through the 'preLights peer support' initiative.

| List by | preLights peer support |

EMBO | EMBL Symposium: The organism and its environment

This preList contains preprints discussed during the 'EMBO | EMBL Symposium: The organism and its environment', organised at EMBL Heidelberg, Germany (May 2023).

| List by | Girish Kale |

Bats

A list of preprints dealing with the ecology, evolution and behavior of bats

| List by | Baheerathan Murugavel |

(1 votes)

(1 votes)

5 years

Andrea Attardi

I find this excellent food for thought, and I’m so glad for having been exposed to this work thanks to your prelight!

Some of the questions you raise seem to challenge the idea that we need to adopt a “lingua franca”, such as English, to be able to communicate research. In fact, we could have research done in many different languages, yet being able to integrate those just by discussing it in groups of polyglot scientists. In a way this would also blur the canonical “boundaries” of research teams and lead us to a more connected, extended community of scholars.