Crowdfunded whole-genome sequencing of the celebrity cat Lil BUB identifies causal mutations for her osteopetrosis and polydactyly

Preprint posted on 22 February 2019 https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/556761v1

What are the chances to suffer from more than one rare disease at the same time? The celebrity cat Lil BUB had it's genome sequenced to be precisely diagnosed with the two rare mutations responsible for her unique phenotype.

Selected by Jesus Victorino, Gabriel Aughey(This preprint was highlighted by Jesus Victorino with the help of Gabriel Aughey)

Background

Rare diseases are a group of disorders that have a low incidence in the population, which often implies reduced interest from public and private entities and, therefore, limited diagnosis and treatment of affected patients.

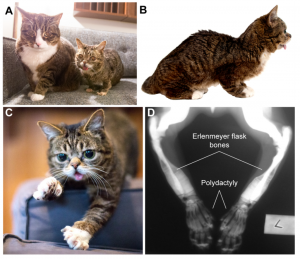

In this study, Bridavsky et al. describe the genome sequence of Lil BUB, a celebrity feline with almost 3 million Facebook followers. Lil BUB has a unique appearance thought to be due to her diagnosed osteopetrosis: a diminutive stature, a distinctive protruding tongue together with a form of polydactyly that makes her have 6 toes on each front paw – all of which contribute to her mass appeal (Fig.1).

Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) was performed thanks to a crowdfunding initiative to fund the study while engaging the public. After sequencing, the authors were able to identify two different mutations, showing that Lil BUB presented not one but two different rare diseases: a homozygous allele for the osteopetrosis phenotype and a polydactylyl allele in heterozygosis.

In this preprint, the authors discover the genetic basis of Lil BUB’s unique phenotypes and furthermore, demonstrate the power of crowdfunding in not only accomplishing scientific goals, but also for public engagement and science dissemination.

Figure 1. Lil BUB complex phenotype showing dwarfism (A), short skull and tongue (B), polydactyly (C) and bone defects in forelimbs (D)(taken from figure 1 of the preprint).

Key findings

-

Successful crowdfunding campaign

Whilst the majority of scientific funding is obtained from competitive grants, Lil’ Bub’s status amongst the internet’s most venerated cats afforded the authors an opportunity to experiment with alternative funding streams for this project. Therefore, the authors embarked on a crowdfunding campaign to cover the costs of sequencing Lil Bub’s genome. Not only was the crowdfunder financially successful (raising over $8000), the opportunity to effectively engage the public with science was also exploited. The authors communicated the aims and progress of the project via various social media platforms, thereby demonstrating that the crowdfunding model can come with societal benefits beyond just the funding of novel research.

-

Lil BUB phenotype is caused by two independent mutations

Osteopetrosis and polydactyly are both rare diseases that have not been linked to one another in humans or cats. Whether Lil-BUB had been affected by an unusual case of osteopetrosis that included polydactyly or by two different rare diseases at the same time was uncertain and this study aimed to answer this and find the genetic causes of her symptoms.

Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) was performed and revealed a heterozygous mutation in the limb enhancer of the Sonic hedgehog gene, already known to be linked to dominant polydactyly in mammals. Osteopetrosis, however, seemed to be caused by a homozygous recessive allele in the TNFRSF11A gene encoding a truncated version of the transmembrane receptor RANK.

Why we like this preprint

The identification of causal mutations in precision medicine constitutes the ultimate goal of NGS-mediated personalized diagnosis. However, due to our restricted knowledge of the genome, determining the clinical significance of mutations in probands is limited to previous reports on similar cases.

We chose this preprint because it is an example of how precision medicine can help fine-tuning a phenotype-based diagnosis thus leading to a more accurate description of a patient’s disease and, if possible, an improvement in the treatment. In this case, Lil BUB’s acute phenotype was the result of two different rare diseases.

Moreover, this work is a beautiful combination of how the creativity and enthusiasm of a committed group of scientists took over possible money burdens and launched an initiative that allowed them not only to fulfill their research purposes, but to reach an audience of tens of thousands of people, who they kept engaged and updated with their scientific advances.

Questions for the authors

– Lil Bub’s celebrity status was clearly important for a successful crowdfunding campaign. Do you think it would be possible to fund a project like this without the existing fanbase that Lil Bub brought with her?

– Are you considering crowdfunding as a periodic way of funding some of your research projects? Would there be a potential danger for projects to become too biased on mediatic research?

– After the success of this research, how do the authors envision the future of crowdfunding in science? Could there be too many projects trying to use this strategy and, thus, many of them fail to succeed?

– What would be the advice for young motivated researchers who want to get both funding and public engagement?

– Many different mutations affecting the ZRS limb enhancer cause ectopic anterior expression of the Shh gene and UK1, UK2 and Hemingway mutations are examples of that [1]. Is it known which transcription factor/s bind the ZRS enhancer? Do the authors think the different mutations affect the same putative binding site?

– ZMPSTE24 is a metalloprotease involved, among other things, in Lamin A maturation and knockout mice have been studied due to the similarities with phenotypes of patients with Progeria syndrome, showing strong phenotypes in mice when in homozygosis [2]. In Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome (HGPS), a heterozygous point mutation affecting a splicing site in LMNA gene that impairs correct Lamin A maturation and causes premature aging. However, while in humans this mutation appears spontaneously and causes severe phenotypes in heterozygosis, the equivalent mutation in mice confers the strong phenotype when the animals are homozygous [3]. Due to the differences in the phenotype effect of heterozygous and homozygous mutations in human and mouse, we were wondering whether the heterozygous loss-of-function allele of ZMPSTE24 has been reported in cats and if the allele found in Lil BUB’s genome could be contributing to her congenital malformations.

References

- Lettice LA, Hill AE, Devenney PS and Hill RE. 2008. Point mutations in a distant sonic hedgehog cis-regulator generate a variable regulatory output responsible for preaxial polydactyly. Hum Mol Genet. 17, 978-985.

- De la Rosa J, Freije JMP, Cabanillas R, Osorio FG, Fraga MF, Fernandez-Garcia MS, Rad R, Fanjul F, Ugalde AP, Liang Q, Prosser HM, Bradley A, Cadiñanos J, Lopez-Otin C. 2013. Prelamin A causes progeria through cell-extrinsic mechanisms and prevents cancer invasion. Nat Comm. 4:2268.

- Osorio FG, Navarro CL, Cadiñanos J, Lopez-Mejia IC, Quirós PM, Bartoli C, Rivera J, Tazi J, Guzman G, Varela I, Depetris D, de Carlos F, Cobo J, Andres V, De Sandre-Giovannoli A, Freije JMP, Levy N, Lopez-Otin C. 2011. Splicing-Directed Therapy in a New Mouse Model ofHuman Accelerated Aging. Sci Transl Med. 3, Issue 106, pp. 106ra107.

Posted on: 21 March 2019 , updated on: 23 March 2019

doi: https://doi.org/10.1242/prelights.9541

Read preprintSign up to customise the site to your preferences and to receive alerts

Register hereAlso in the genetics category:

Temporal constraints on enhancer usage shape the regulation of limb gene transcription

A long non-coding RNA at the cortex locus controls adaptive colouration in butterflies

AND

The ivory lncRNA regulates seasonal color patterns in buckeye butterflies

AND

A micro-RNA drives a 100-million-year adaptive evolution of melanic patterns in butterflies and moths

A revised single-cell transcriptomic atlas of Xenopus embryo reveals new differentiation dynamics

Also in the genomics category:

Temporal constraints on enhancer usage shape the regulation of limb gene transcription

Transcriptional profiling of human brain cortex identifies novel lncRNA-mediated networks dysregulated in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

A long non-coding RNA at the cortex locus controls adaptive colouration in butterflies

AND

The ivory lncRNA regulates seasonal color patterns in buckeye butterflies

AND

A micro-RNA drives a 100-million-year adaptive evolution of melanic patterns in butterflies and moths

preLists in the genetics category:

BSDB/GenSoc Spring Meeting 2024

A list of preprints highlighted at the British Society for Developmental Biology and Genetics Society joint Spring meeting 2024 at Warwick, UK.

| List by | Joyce Yu, Katherine Brown |

BSCB-Biochemical Society 2024 Cell Migration meeting

This preList features preprints that were discussed and presented during the BSCB-Biochemical Society 2024 Cell Migration meeting in Birmingham, UK in April 2024. Kindly put together by Sara Morais da Silva, Reviews Editor at Journal of Cell Science.

| List by | Reinier Prosee |

9th International Symposium on the Biology of Vertebrate Sex Determination

This preList contains preprints discussed during the 9th International Symposium on the Biology of Vertebrate Sex Determination. This conference was held in Kona, Hawaii from April 17th to 21st 2023.

| List by | Martin Estermann |

Alumni picks – preLights 5th Birthday

This preList contains preprints that were picked and highlighted by preLights Alumni - an initiative that was set up to mark preLights 5th birthday. More entries will follow throughout February and March 2023.

| List by | Sergio Menchero et al. |

Semmelweis Symposium 2022: 40th anniversary of international medical education at Semmelweis University

This preList contains preprints discussed during the 'Semmelweis Symposium 2022' (7-9 November), organised around the 40th anniversary of international medical education at Semmelweis University covering a wide range of topics.

| List by | Nándor Lipták |

20th “Genetics Workshops in Hungary”, Szeged (25th, September)

In this annual conference, Hungarian geneticists, biochemists and biotechnologists presented their works. Link: http://group.szbk.u-szeged.hu/minikonf/archive/prg2021.pdf

| List by | Nándor Lipták |

2nd Conference of the Visegrád Group Society for Developmental Biology

Preprints from the 2nd Conference of the Visegrád Group Society for Developmental Biology (2-5 September, 2021, Szeged, Hungary)

| List by | Nándor Lipták |

EMBL Conference: From functional genomics to systems biology

Preprints presented at the virtual EMBL conference "from functional genomics and systems biology", 16-19 November 2020

| List by | Jesus Victorino |

TAGC 2020

Preprints recently presented at the virtual Allied Genetics Conference, April 22-26, 2020. #TAGC20

| List by | Maiko Kitaoka et al. |

ECFG15 – Fungal biology

Preprints presented at 15th European Conference on Fungal Genetics 17-20 February 2020 Rome

| List by | Hiral Shah |

Autophagy

Preprints on autophagy and lysosomal degradation and its role in neurodegeneration and disease. Includes molecular mechanisms, upstream signalling and regulation as well as studies on pharmaceutical interventions to upregulate the process.

| List by | Sandra Malmgren Hill |

Zebrafish immunology

A compilation of cutting-edge research that uses the zebrafish as a model system to elucidate novel immunological mechanisms in health and disease.

| List by | Shikha Nayar |

Also in the genomics category:

BSCB-Biochemical Society 2024 Cell Migration meeting

This preList features preprints that were discussed and presented during the BSCB-Biochemical Society 2024 Cell Migration meeting in Birmingham, UK in April 2024. Kindly put together by Sara Morais da Silva, Reviews Editor at Journal of Cell Science.

| List by | Reinier Prosee |

preLights peer support – preprints of interest

This is a preprint repository to organise the preprints and preLights covered through the 'preLights peer support' initiative.

| List by | preLights peer support |

9th International Symposium on the Biology of Vertebrate Sex Determination

This preList contains preprints discussed during the 9th International Symposium on the Biology of Vertebrate Sex Determination. This conference was held in Kona, Hawaii from April 17th to 21st 2023.

| List by | Martin Estermann |

Semmelweis Symposium 2022: 40th anniversary of international medical education at Semmelweis University

This preList contains preprints discussed during the 'Semmelweis Symposium 2022' (7-9 November), organised around the 40th anniversary of international medical education at Semmelweis University covering a wide range of topics.

| List by | Nándor Lipták |

20th “Genetics Workshops in Hungary”, Szeged (25th, September)

In this annual conference, Hungarian geneticists, biochemists and biotechnologists presented their works. Link: http://group.szbk.u-szeged.hu/minikonf/archive/prg2021.pdf

| List by | Nándor Lipták |

EMBL Conference: From functional genomics to systems biology

Preprints presented at the virtual EMBL conference "from functional genomics and systems biology", 16-19 November 2020

| List by | Jesus Victorino |

TAGC 2020

Preprints recently presented at the virtual Allied Genetics Conference, April 22-26, 2020. #TAGC20

| List by | Maiko Kitaoka et al. |

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)