Integrated NMR and cryo-EM atomic-resolution structure determination of a half-megadalton enzyme complex

Posted on: 5 January 2019 , updated on: 18 February 2019

Preprint posted on 16 December 2018

Article now published in Nature Communications at http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10490-9

It takes two to tango: the combined power of cryo-EM and NMR for protein structure determination

Selected by Reid AldersonCategories: biochemistry, biophysics

Background

The three-dimensional (3D) structures of proteins and nucleic acids provide fundamental insight into biological processes. Being able to ‘see’ the precise arrangement of atoms within a molecule offers an unprecedented view of its function: e.g., writing about the double helix structure of DNA in 1953, Watson and Crick [1] noted that it “immediately suggests a possible copying mechanism for the genetical material.” Due to the unparalleled level of detail derived from biological structures, numerous Nobel prizes have been awarded on this topic, including those for DNA, ribosomes, DNA and RNA polymerases, and G-protein coupled receptors.

Biomolecular structures can be determined at atomic resolution by one of three experimental methods: X-ray crystallography (XRC), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy in the solution- or solid-state, or single-particle cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM). In principle, XRC is not limited by the mass of the molecule, whereas both cryo-EM and solution-state NMR are confined at present to solving structures of molecules > 50-100 kDa and < 60 kDa, respectively, due to instrumental and physical restrictions. Solid-state NMR is not hindered by the mass of the molecule, but practical limitations due to the sheer number of detected signals and their signal overlap have mired progress on large monomeric proteins or oligomers with large subunits.

XRC is the most commonly employed technique in structural biology, as over 90% of the ca. 150,000 structures in the Protein DataBank (PDB) have been solved by this method. Despite the widespread usage of XRC, its main limitation lies in its requirement for a crystal, the “quality” of which directly impacts the final resolution (or quality) of an X-ray structure. Large biomolecules often require precise, finely tuned crystallization conditions (pH, ionic strength, temperature, buffer, precipitants, etc.), which are not known a priori. Therefore, many crystallization conditions – sometimes thousands – must be empirically screened to obtain crystals that yield high-resolution structures. Furthermore, the difficulty in crystallization generally increases with the mass and complexity of a target, evidenced by the fact that only ca. 23% of the structured solved by XRC in the PDB exceed 100 kDa, even though most proteins exist as large oligomers: it is estimated that 60-80% of proteins oligomerize [4]. A review on protein structures noted that the PDB “over represents small monomers” due to the difficulties in crystallizing larger proteins and their complexes [5]. Finally, some proteins are recalcitrant to crystallization because they exist in multiple conformations with considerable flexibility.

NMR and cryo-EM circumvent the need for crystallization, but these two methods have only contributed to roughly 10% of the PDB structures. This is largely due to experimental limitations in solution-state NMR that limit the size of molecule amenable to structure determination and to a recent “resolution revolution” in cryo-EM, which originated with the development of better instruments, new electron detectors (direct electron detectors), and new algorithms and analysis methods [2, 3]. However, some proteins are structural biologists’ worst nightmares: proteins that are not amenable to crystallization, yield low-quality NMR spectra, and are too conformationally heterogenous for cryo-EM. Obtaining de novo atomic-resolution structures of such proteins is extremely challenging, if not impossible; however, results from various biophysical methods, which on their own are incapable of determining a de novo structure, can be integrated to determine a structural model that satisfies the maximum number of experimental restraints. This process has become common enough to be named: integrative structural biology or integrative modeling [6]. Software programs such as HADDOCK [7] and the Integrative Modeling Platform [6] collate results from mass spectrometry, electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR), Forster resonance energy transfer (FRET), small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS), and other techniques to determine accurate structural models, although the final structures are themselves not atomic-resolution structures.

There is a need in structural biology to obtain high- or atomic-resolution structures of proteins and their complexes that are not amenable to traditional approaches. This preprint by Gauto et al. [8] tackles that problem by taking a similar approach to integrative modeling, but goes one step further: can limited datasets from two methods that are capable of de novo structure determination (NMR and cryo-EM) be combined to solve an atomic-resolution or near atomic-resolution structure, even when the datasets on their own are insufficient for a de novo structure? If yes, how much data are required and of what quality?

Experimental aspects

Since this preprint largely relies on data from NMR spectroscopy and cryo-EM, I will briefly discuss experimental aspects of these methods before discussing the results. NMR spectroscopy and cryo-EM are highly complementary. Lower-resolution cryo-EM maps can provide access to global structural details such as the diameter of a complex or oligomer, its overall symmetry, and the location of structural features like α-helices – pieces of information that are useful for structural modeling even if a de novo structure cannot be obtained from the cryo-EM data. Complementarily, NMR data yield more local information about the molecule of interest, including identifying regions of secondary structural elements, residues that are flexible or dynamic, and nuclei that are close together in space (< ca. 5-10 Å depending on the experiment). Furthermore, solution- and solid-state NMR are themselves also highly complementary. While solution-state NMR is limited to solving structures of molecules < 60 kDa, data can still be collected on molecules near and in excess of 1 MDa [9, 10] ; however, only the NMR signals from a subset of nuclei in a highly deuterated molecule can be detected (generally methyl groups), thereby limiting the information content and rendering structure determination unfeasible. Despite this limitation, methyl-based NMR experiments on large proteins have revolutionized solution-state NMR studies [9]. In combination with a previously determined atomic resolution structure, methyl-based NMR data in the solution state enable highly detailed mechanistic structure/function studies [9].

In solid-state NMR, there is no limit on the mass of the molecule, but issues with signal overlap and broad signals become worse with increasing mass. Recent developments in solid-state NMR hardware and detection methods, however, have provided a breakthrough in the field, providing significantly higher resolution and pushing the field to new frontiers [11]. Feats such as determining the structures of amyloid fibrils and other filamentous structures with solid-state NMR are now feasible [11]. Notably, there has long been collaboration between EM and solid-state NMR. One caveat of NMR studies (both solution- and solid-state) is that it requires a large amount of isotopically labeled protein (enriched in 13C, 15N, and/or 2H) – hundreds of micromolar or more – and so the protein must be able to be prepared in bacterial, yeast, or inset cells. Isotope labeling strategies in mammalian cells are currently rather cost-prohibitive.

Results of the preprint

In order to assess the ability of a joint cryo-EM and NMR dataset for structure determination, the authors collected EM maps and solution- and solid-state NMR data on a symmetric dodecamer named TET2 (12 x 39 kDa), a protease totaling 468 kDa in mass. The data comprised an EM map at 4.1 Å that was blurred to create 6 Å and 8 Å maps; intra-subunit contacts between the methyl groups of Ile and Val residues, as measured by solution-state NMR; and an extensive set of solid-state NMR data encompassing backbone and side-chain chemical shift assignments (85% and 70% complete, respectively) – from which the secondary structure elements were determined (via the backbone torsion angles φ and ψ) – and inter-nuclear distances including amide-amide, amide-ILV methyl, ILV methyl-ILV methyl, and aliphatic-aliphatic contacts, for a total of 471 specific and 45 ambiguous contacts [8]. As an aside, the 39 kDa subunit of TET2 makes it the largest subunit with near-complete backbone chemical shift assignments determined solid-state NMR, as typically solid-state NMR studies make use of large oligomers that have small subunits to take advantage of chemical equivalence and symmetry (fewer NMR signals).

Neither the EM nor the NMR datasets on their own could determine a de novo structure of the TET2 oligomer [8]. The 4.1 Å EM map may have been able to yield a structure if the authors pursued a careful manual analysis, but a commonly employed software (phenix) failed to automatically build the polypeptide chain from this map. As such, the authors developed a joint EM/NMR structure determination method that utilized the following steps: (1) identify structural elements (α-helices) in the EM map, (2) use NMR data to identify structural regions in the amino acid sequence, (3) map the information from step 2 (NMR) to step 1 (EM) and assign structural features to particular regions of the protein sequence, and (4) use the EM and NMR data together to iteratively calculate and refine the protein structure [8].

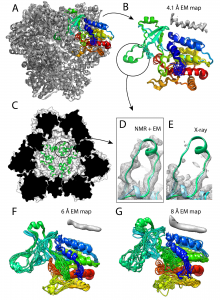

In the end, the authors determined a structure that has a backbone root-mean-square-deviation (RMSD) of 0.7 Å with respect to the crystal structure (Figure 1), which itself had a 1.75 Å resolution [12]. This structure determination made use of the 4.1 Å EM map, although it is important to note that steps 1 and 3 utilized the 8 Å EM map, and only the final step used the high-resolution EM data. Thus, the authors investigated the impact of lower resolution EM maps, and re-calculated the structure by using either the 6 or 8 Å EM map in the final step (using the 8 Å map for steps 1 and 3, as before). The final backbone RMSD values to the crystal structure were 1.7 and 2.6 Å, respectively, for the 6 and 8 Å EM maps [8]. Since the average resolution in the EM database (EMDB) in the year 2018 was 6.6 Å [8], the 6 and 8 Å EM maps represent slightly above and slightly below average EM datasets. The final structures calculated from these data are still near atomic-resolution and represent a considerable improvement over integrative modeling approaches based on lower-resolution data.

Finally, the usage of cryo-EM enabled identification of a previously unobserved loop near the catalytic chamber of the TET2 oligomer (Figure 1). The stretch of residues 119-138 did not yield electron density in the X-ray structure; however, the region was readily identifiable in the current EM map and thus present in their new structure. The solid-state NMR chemical shifts for this region were not observed or not assigned, likely meaning that this loop is ordered at cryogenic temperatures but dynamically disordered at room temperature, which is consistent with its lack of electron density in the X-ray structure.

Figure 1. Structure of the TET2 dodecamer obtained from the EM/NMR integrative modeling method. (A) Final structure of TET2 using the 4.1 Å EM map showing all 12 subunits. (B) Zoomed-in structure of a single subunit from panel A. Shown here are 10 overlaid structures of one monomer with an average backbone RMSD of 0.7 Å relative to the 1.75 Å crystal structure. The dynamic loop is circled. (C) The dynamic loop region in the interior of the cavity of the NMR/EM structure. (D) and (E) Show a comparison of the dynamic loop region in the NMR/EM structure (green) to the X-ray structure (light blue), with density corresponding to the EM map and X-ray structure, respectively. (F) and (G) The same as panel B except for the usage of the 6 Å or 8 Å EM map, respectively. The average backbone RMSD values for F and G relative to the X-ray structure are respectively 1.7 and 2.6 Å. This is Figure 4 from the preprint, which is reproduced here under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license.

What I like about this preprint

I like that this preprint combined structural data from two different, but highly powerful and complementary methods to produce a new integrative modeling platform. Cryo-EM has been all the rage over the past few years, but it will not be the answer to all problems in structural biology. For instance, the authors note [8] that, in the year 2016 when nearly 1000 new EM maps were deposited in the EM database (EMDB), only 20% had a resolution below 3.5 Å, which would be suitable for atomic-resolution, de novo structure determination. In addition, out of the 20% of maps with < 3.5 Å resolution, ca. 60% of them were obtained from samples of viruses, ribosomes, or proteins with known crystal structures (personal communication with P.S.). Ribosomes and viruses are highly favorable EM targets, and therefore only a very limited number of atomic-resolution EM maps were obtained for non-ribosome or non-virus targets.

Accordingly, the authors investigated the impact of the resolution of the EM map, especially lower-resolution data, on the outcome of their new integrative modeling method. This represents more of a ‘real world’ situation, where the EM data may not be perfect or able to solve a structure on its own. Despite lower-resolution EM maps, the authors showed that, in combination with NMR data, they could determine a TET2 dodecameric structure that was within 1.7-2.6 Å of the 1.75 Å crystal structure. This new approach to solving large structures combines the best aspects of cryo-EM and NMR, yielding an integrative approach that is more powerful than either method on its own.

References

- Watson J.D., Crick F.H.C. (1953) Molecular structure of nucleic acids: a structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid. Nature 171: 737-738

- McMullan G., Faruqi A.R., Henderson R. (2016) Direct electron detectors. Methods Enzymol. 579: 1-17.

- Cheng Y. (2018) Single-particle cryo-EM – How did it get here and where will it go? Science 361: 876-880.

- Goodsell D.S., Olson A.J. (2000) Structural symmetry and protein function. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 29: 105-153.

- Jones S., Thornton J.M. (1996) Principles of protein-protein interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93: 13-20.

- Russel D., Lasker K., Webb B., Velazquez-Muriel, J., Tjioe, E., Schneidman-Duhovny D., Peterson, B., Sali, A. (2012) Putting the pieces together: integrative modeling platform software for structure determination of macromolecular assemblies. PLoS Biol. 10: e1001244.

- van Zundert G.C.P., Rodrigues J.P.G.L.M, Trellet M., Schmitz C., Kastritis P.L., Karaca E., Melquiond A.S.J., van Dijk M., de Vries S.J., Bonvin A.M.J.J. (2016) The HADDOCK2.2 web server: user-friendly integrative modeling of biomolecular complexes. J. Mol. Biol. 428: 720-725.

- Gauto D., Estrozi L, Schwieters C., Effantin G., Macek P., Sounier R., Sivertsen A.C., Schmidt E., Kerfah R., Mas G., Colletier J.-P., Guntert P., Favier A., Schoehn G., Boisbouvier J., Schanda P. (2018) Integrated NMR and cryo-EM atomic-resolution structure of a half-megadalton enzyme complex. bioRxiv https://www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2018/12/16/498287

- Rosenzweig R., Kay L.E. (2014) Bringing dynamic molecular machines into focus by methyl-TROSY NMR. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 83: 291-315.

- Fiaux J., Bertelsen E.B., Horwich A.L., Wuthrich K. (2002) NMR analysis of a 900K GroEL-GroES complex. Nature 418: 207-211.

- Demers J.-P., Fricke P., Shi C., Chevelkov V., Lange A. (2018) Structure determination of supra-molecular assemblies by solid-state NMR: practical considerations. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 109: 51-78.

- Borissenko L., Groll M. (2005) Crystal structure of TET protease reveals complementary protein degradation pathways in prokaryotes. J. Mol. Biol. 346: 1207-1219.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1242/prelights.6921

Read preprintSign up to customise the site to your preferences and to receive alerts

Register hereAlso in the biochemistry category:

Active flows drive clustering and sorting of membrane components with differential affinity to dynamic actin cytoskeleton

Teodora Piskova

Snake venom metalloproteinases are predominantly responsible for the cytotoxic effects of certain African viper venoms

Daniel Osorno Valencia

Cryo-EM reveals multiple mechanisms of ribosome inhibition by doxycycline

Leonie Brüne

Also in the biophysics category:

Active flows drive clustering and sorting of membrane components with differential affinity to dynamic actin cytoskeleton

Teodora Piskova

Junctional Heterogeneity Shapes Epithelial Morphospace

Bhaval Parmar

Mitochondrial Fatty Acid Oxidation is Stimulated by Red Light Irradiation

Rickson Ribeiro, Marcus Oliveira

preLists in the biochemistry category:

September in preprints – Cell biology edition

A group of preLighters, with expertise in different areas of cell biology, have worked together to create this preprint reading list. This month, categories include: (1) Cell organelles and organisation, (2) Cell signalling and mechanosensing, (3) Cell metabolism, (4) Cell cycle and division, (5) Cell migration

| List by | Sristilekha Nath et al. |

July in preprints – the CellBio edition

A group of preLighters, with expertise in different areas of cell biology, have worked together to create this preprint reading lists for researchers with an interest in cell biology. This month, categories include: (1) Cell Signalling and Mechanosensing (2) Cell Cycle and Division (3) Cell Migration and Cytoskeleton (4) Cancer Biology (5) Cell Organelles and Organisation

| List by | Girish Kale et al. |

June in preprints – the CellBio edition

A group of preLighters, with expertise in different areas of cell biology, have worked together to create this preprint reading lists for researchers with an interest in cell biology. This month, categories include: (1) Cell organelles and organisation (2) Cell signaling and mechanosensation (3) Genetics/gene expression (4) Biochemistry (5) Cytoskeleton

| List by | Barbora Knotkova et al. |

May in preprints – the CellBio edition

A group of preLighters, with expertise in different areas of cell biology, have worked together to create this preprint reading lists for researchers with an interest in cell biology. This month, categories include: 1) Biochemistry/metabolism 2) Cancer cell Biology 3) Cell adhesion, migration and cytoskeleton 4) Cell organelles and organisation 5) Cell signalling and 6) Genetics

| List by | Barbora Knotkova et al. |

Keystone Symposium – Metabolic and Nutritional Control of Development and Cell Fate

This preList contains preprints discussed during the Metabolic and Nutritional Control of Development and Cell Fate Keystone Symposia. This conference was organized by Lydia Finley and Ralph J. DeBerardinis and held in the Wylie Center and Tupper Manor at Endicott College, Beverly, MA, United States from May 7th to 9th 2025. This meeting marked the first in-person gathering of leading researchers exploring how metabolism influences development, including processes like cell fate, tissue patterning, and organ function, through nutrient availability and metabolic regulation. By integrating modern metabolic tools with genetic and epidemiological insights across model organisms, this event highlighted key mechanisms and identified open questions to advance the emerging field of developmental metabolism.

| List by | Virginia Savy, Martin Estermann |

April in preprints – the CellBio edition

A group of preLighters, with expertise in different areas of cell biology, have worked together to create this preprint reading lists for researchers with an interest in cell biology. This month, categories include: 1) biochemistry/metabolism 2) cell cycle and division 3) cell organelles and organisation 4) cell signalling and mechanosensing 5) (epi)genetics

| List by | Vibha SINGH et al. |

Biologists @ 100 conference preList

This preList aims to capture all preprints being discussed at the Biologists @100 conference in Liverpool, UK, either as part of the poster sessions or the (flash/short/full-length) talks.

| List by | Reinier Prosee, Jonathan Townson |

February in preprints – the CellBio edition

A group of preLighters, with expertise in different areas of cell biology, have worked together to create this preprint reading lists for researchers with an interest in cell biology. This month, categories include: 1) biochemistry and cell metabolism 2) cell organelles and organisation 3) cell signalling, migration and mechanosensing

| List by | Barbora Knotkova et al. |

Community-driven preList – Immunology

In this community-driven preList, a group of preLighters, with expertise in different areas of immunology have worked together to create this preprint reading list.

| List by | Felipe Del Valle Batalla et al. |

January in preprints – the CellBio edition

A group of preLighters, with expertise in different areas of cell biology, have worked together to create this preprint reading lists for researchers with an interest in cell biology. This month, categories include: 1) biochemistry/metabolism 2) cell migration 3) cell organelles and organisation 4) cell signalling and mechanosensing 5) genetics/gene expression

| List by | Barbora Knotkova et al. |

BSCB-Biochemical Society 2024 Cell Migration meeting

This preList features preprints that were discussed and presented during the BSCB-Biochemical Society 2024 Cell Migration meeting in Birmingham, UK in April 2024. Kindly put together by Sara Morais da Silva, Reviews Editor at Journal of Cell Science.

| List by | Reinier Prosee |

Peer Review in Biomedical Sciences

Communication of scientific knowledge has changed dramatically in recent decades and the public perception of scientific discoveries depends on the peer review process of articles published in scientific journals. Preprints are key vehicles for the dissemination of scientific discoveries, but they are still not properly recognized by the scientific community since peer review is very limited. On the other hand, peer review is very heterogeneous and a fundamental aspect to improve it is to train young scientists on how to think critically and how to evaluate scientific knowledge in a professional way. Thus, this course aims to: i) train students on how to perform peer review of scientific manuscripts in a professional manner; ii) develop students' critical thinking; iii) contribute to the appreciation of preprints as important vehicles for the dissemination of scientific knowledge without restrictions; iv) contribute to the development of students' curricula, as their opinions will be published and indexed on the preLights platform. The evaluations will be based on qualitative analyses of the oral presentations of preprints in the field of biomedical sciences deposited in the bioRxiv server, of the critical reports written by the students, as well as of the participation of the students during the preprints discussions.

| List by | Marcus Oliveira et al. |

CellBio 2022 – An ASCB/EMBO Meeting

This preLists features preprints that were discussed and presented during the CellBio 2022 meeting in Washington, DC in December 2022.

| List by | Nadja Hümpfer et al. |

20th “Genetics Workshops in Hungary”, Szeged (25th, September)

In this annual conference, Hungarian geneticists, biochemists and biotechnologists presented their works. Link: http://group.szbk.u-szeged.hu/minikonf/archive/prg2021.pdf

| List by | Nándor Lipták |

Fibroblasts

The advances in fibroblast biology preList explores the recent discoveries and preprints of the fibroblast world. Get ready to immerse yourself with this list created for fibroblasts aficionados and lovers, and beyond. Here, my goal is to include preprints of fibroblast biology, heterogeneity, fate, extracellular matrix, behavior, topography, single-cell atlases, spatial transcriptomics, and their matrix!

| List by | Osvaldo Contreras |

ASCB EMBO Annual Meeting 2019

A collection of preprints presented at the 2019 ASCB EMBO Meeting in Washington, DC (December 7-11)

| List by | Madhuja Samaddar et al. |

EMBL Seeing is Believing – Imaging the Molecular Processes of Life

Preprints discussed at the 2019 edition of Seeing is Believing, at EMBL Heidelberg from the 9th-12th October 2019

| List by | Dey Lab |

Cellular metabolism

A curated list of preprints related to cellular metabolism at Biorxiv by Pablo Ranea Robles from the Prelights community. Special interest on lipid metabolism, peroxisomes and mitochondria.

| List by | Pablo Ranea Robles |

MitoList

This list of preprints is focused on work expanding our knowledge on mitochondria in any organism, tissue or cell type, from the normal biology to the pathology.

| List by | Sandra Franco Iborra |

Also in the biophysics category:

October in preprints – DevBio & Stem cell biology

Each month, preLighters with expertise across developmental and stem cell biology nominate a few recent developmental and stem cell biology (and related) preprints they’re excited about and explain in a single paragraph why. Short, snappy picks from working scientists — a quick way to spot fresh ideas, bold methods and papers worth reading in full. These preprints can all be found in the October preprint list published on the Node.

| List by | Deevitha Balasubramanian et al. |

October in preprints – Cell biology edition

Different preLighters, with expertise across cell biology, have worked together to create this preprint reading list for researchers with an interest in cell biology. This month, most picks fall under (1) Cell organelles and organisation, followed by (2) Mechanosignaling and mechanotransduction, (3) Cell cycle and division and (4) Cell migration

| List by | Matthew Davies et al. |

March in preprints – the CellBio edition

A group of preLighters, with expertise in different areas of cell biology, have worked together to create this preprint reading lists for researchers with an interest in cell biology. This month, categories include: 1) cancer biology 2) cell migration 3) cell organelles and organisation 4) cell signalling and mechanosensing 5) genetics and genomics 6) other

| List by | Girish Kale et al. |

Biologists @ 100 conference preList

This preList aims to capture all preprints being discussed at the Biologists @100 conference in Liverpool, UK, either as part of the poster sessions or the (flash/short/full-length) talks.

| List by | Reinier Prosee, Jonathan Townson |

February in preprints – the CellBio edition

A group of preLighters, with expertise in different areas of cell biology, have worked together to create this preprint reading lists for researchers with an interest in cell biology. This month, categories include: 1) biochemistry and cell metabolism 2) cell organelles and organisation 3) cell signalling, migration and mechanosensing

| List by | Barbora Knotkova et al. |

preLights peer support – preprints of interest

This is a preprint repository to organise the preprints and preLights covered through the 'preLights peer support' initiative.

| List by | preLights peer support |

66th Biophysical Society Annual Meeting, 2022

Preprints presented at the 66th BPS Annual Meeting, Feb 19 - 23, 2022 (The below list is not exhaustive and the preprints are listed in no particular order.)

| List by | Soni Mohapatra |

EMBL Synthetic Morphogenesis: From Gene Circuits to Tissue Architecture (2021)

A list of preprints mentioned at the #EESmorphoG virtual meeting in 2021.

| List by | Alex Eve |

Biophysical Society Meeting 2020

Some preprints presented at the Biophysical Society Meeting 2020 in San Diego, USA.

| List by | Tessa Sinnige |

ASCB EMBO Annual Meeting 2019

A collection of preprints presented at the 2019 ASCB EMBO Meeting in Washington, DC (December 7-11)

| List by | Madhuja Samaddar et al. |

EMBL Seeing is Believing – Imaging the Molecular Processes of Life

Preprints discussed at the 2019 edition of Seeing is Believing, at EMBL Heidelberg from the 9th-12th October 2019

| List by | Dey Lab |

Biomolecular NMR

Preprints related to the application and development of biomolecular NMR spectroscopy

| List by | Reid Alderson |

Biophysical Society Annual Meeting 2019

Few of the preprints that were discussed in the recent BPS annual meeting at Baltimore, USA

| List by | Joseph Jose Thottacherry |

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)